“Nobody made a greater mistake than doing nothing because he could only do a little.”

– Edmund Burke

In philosophy, a sublime tragedy is any endeavor doomed to fail. However, the manner of that failure must be beautiful to behold, such that—despite the failure itself—the endeavor seemed worthwhile.

The Jamaican Bobsled Team, for example, was seen as a group of laughable underdogs in their first Olympic appearance. Even though they failed to place in the games, their heart inspired many world citizens—not the least of which were their Jamaican countrymen who had often been told they were of inferior athletic caliber. It took several years, but Jamaica actually placed first in the 2000 World Push Championships in Monaco and Team Captain, Lascelles Brown, medaled as part of the Canadian Olympic bobsled team in both the 2006 and 2010 Winter Games.

At the Summer Olympics in 1992, 400m runner Derek Redmond from Great Britain pulled a hamstring during the finals of his heat but refused to quit. Though it took Redmond nearly an additional sixty seconds to hobble across the finish line, he was determined to finish the race. Seeing his son struggle, Derek’s father left the stands and helped his son across the line.

Derek didn’t even come close to winning, and his father’s participation disqualified him anyway. But his story inspired several commercials and short films and even motivated Redmond to persist in his athletic career—going on to play both basketball and rugby for England’s national teams during the following decade.

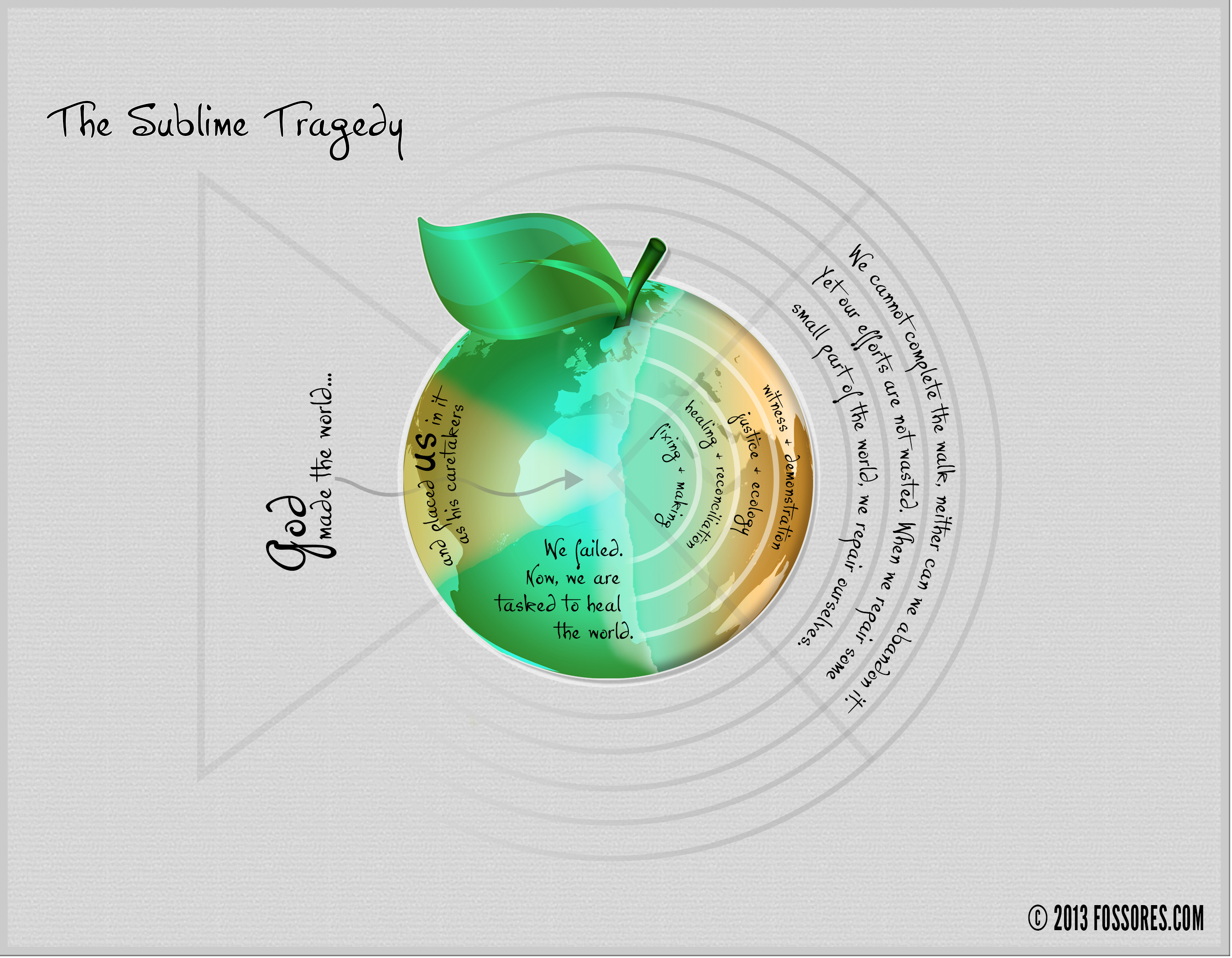

Humans live in the midst of a sublime tragedy.

God created the world and placed us within it to look after it. We did not. Now we are called to heal the world, but that task is too big. The very thing we’re supposed to do we can’t do.

We cannot complete the work, and neither can we abandon it.

But our efforts are not wasted. Some might pout. Some might quit. Some might blame. Some might rage. But not you—your failures will be beautiful and worthwhile because you know the way in which we fail matters.

The good news is that we don’t have to do it all alone; we only have to do what God has ordained for us.

There’s a fascinating detail in Exodus 30.12-13 about our limitations and responsibilities. Having led the Israelites out of Egyptian bondage, Moses must organize them into a new people, and this will require a census. Normally a census was viewed as something terrible, since Israel was always the smallest of the nations and their numbers were guaranteed to depress. Yet God instructs Moses that each adult must make an atonement offering, demonstrating that the strength of God’s people will not be measured by their numbers but by their contribution.

But—and this is important—it’s not much. Just a half-shekel, which, in today’s currency, is about three dollars. Moses was pointing out that even our offerings are not whole by themselves—just “half” an offering—and we need the contribution of others for even our own gifts to add up.

There is a word in Hebrew, Simhah, that we often translate as “joy.” But that’s not quite it. Simhah refers to the happiness we share and the happiness we make by sharing. It is a word about companionship and friendship, solidarity and laughter, trust and tears. It is a half-shekel word, finding satisfaction and completion in the addition of the other half.

We don’t have to fix everyone on our own. We can’t. But we can’t use our lack of total self-sufficiency as an excuse to do nothing. We’ve got to throw in our half-shekel, even if we’re frustrated that it’s not more, even if we’re embarrassed it’s not enough.

When we repair some small part of the world, we repair ourselves.

“Even the youth get tired and weary, and young men stumble and fall; but those who hope in the lord will renew their strength; they will rise on wings like eagles, they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not faint.”

Isaiah 40:30-31

To read the first part of this series, click here.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018