“We know God less by contemplation than by emulation.”

– Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

In Genesis we’re told mankind (Adam) was fashioned from the dust of the earth (Adamah). From the very beginning there was a connection between people and planet. In fact, the word “human” literally means “of the earth.” That’s part of what it means to be human—to look after the world.

But there’s more to it than that, of course. Take the word “humane”, for example. It’s a word we use to refer to benevolent action. To be “humane” literally means “to have qualities benefitting human beings.” Humane people are those who embody the noblest of human virtues.

The Humane Society was founded as a society of lifeguards in Britain. Over time, they became more concerned with animal rescue than drowning swimmers, but the fact remains that they are good. They are caretakers. They are preservers. They are rescuers. They are heroes.

Our world is desperately short of heroes. In Africa I watched as dozens of unfortunates were called “useless” and “unworthy” by those with ample means to help. I have seen similar behavior in Canada, in Germany, and in Michigan.

But that’s not the worst of it.

Yesterday I listened as a friend told me about the rape of a nine-year-old girl at the hands of a child pornographer (who then sold the video online). Two days ago I read an article about parents in the southern states who kept their children in a cage in the basement until the imprisoned little girls ate enough of their own bodies that they were able to slip through the bars and escape.

Our world is sick, and we have forgotten what it means to be human. As a species, we are rarely noble and even less frequently humane.

I used to think that the world would make better sense once I got older. But now I’m older, and the world keeps getting more complicated. I’m more aware of the brokenness. The severity of fragmentation is way, way worse than I ever thought.

Some might contend that humanity is better off than we were two hundred years ago. After all, there have been considerable advances in medical science, communication, and information technology. But I’m not sure that our root problem has been addressed. If a husband beats his wife, does she care about their new computer? If we keep fighting wars, at what point does our ability to heal wounds enable us to continue causing them?

And yet, we’re aware that our existence is impoverished. We know we’re meant to find meaning and purpose in this life. We want it. We wonder who can tell us what it is.

A few years back I purchased a new piece of hardware equipment to interface my computer with my electric guitar. I had a difficult time getting it to work, so I called my friend Mike—who happened to be on the development team that built the device. In less than five minutes, Mike showed me absolutely everything about what the device could do and how it worked.

Because he made it.

You want to know what you’re made to do? Why not ask your Creator?

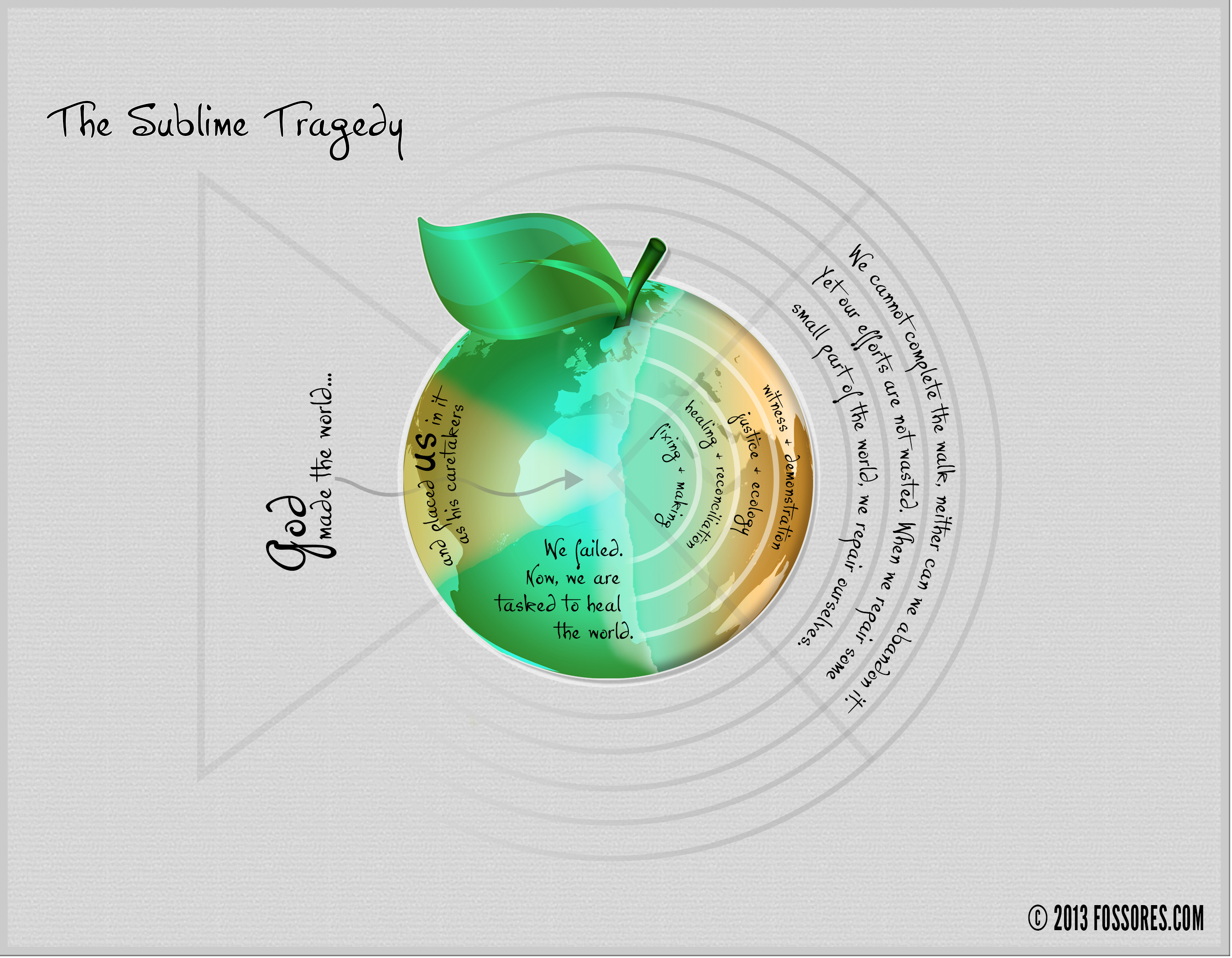

You and I were made to look after the world as God’s shadows and stewards, his “looking-after creatures.” We failed. The world is cracked. Broken. Fragmented. Wounded. Blasted.

But God has not let us off the hook. He refuses to remove our responsibilities simply because we failed to execute them faithfully the first time. So we are now called to heal the world we have broken, much like a child is required to clean up a mess he made in the yard.

We are called to (re)create the world. What has been broken must now be made whole. Smarty-pants people refer to this as participatory eschatology. Eschatology is the study of last things. But the word “last” doesn’t mean “final.” It means “ultimate.” Eschatology, then, is the study of God’s intended climax for Creation. And we participate in that climax. He doesn’t mean for us to sit back and watch the show. We are the show. He has been working in us and with us and through us for a very long time.

We are called kings and priests, designed to reign with God (Revelation 5.10), and the manner of our rule and authority is that we perform good works God has prepared for us since the beginning (see Ephesians 2.10).

Participatory eschatology involves a twofold affirmation: we are to do it with God, and we cannot do it without God. In St. Augustine’s brilliant aphorism, God without us will not; we without God cannot.

For the second part of this series, click here.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018