Do you know what the phrase “Jesus H.Christ” refers to?

These days, it’s terribly offensive- a very high level of profanity; but, its origins are actually quite sacred. It comes from the latiniesus Hominum Salvator,which means: Jesus, Savior of all Mankind.

Now, I confess I’m fascinated at the progression from doctrinal statement to course language. What has happened in our world that we could take something so profound as a summary of the Incarnational theology of Christian spirituality and reduce it to something so profane?

How did the profound become the profane?

Sad, isn’t it? Oversimplification of the gospel story in our culture has robbed the mystery, richness, and transcendence from Jesus’ atoning work on the cross.

And so have we.

To a lesser (and less profane) degree, the Western Church has robbed the person and work of Jesus Christ from all significance except the most basic, cash-transaction version-of-salvation possible. All we ever teach is that Jesus died for our sins so we could be saved. In doing so, we’ve simplified the profound into the mundane. Now, that’s not to say that we’re wrong to present Christ as our savior or our debt-payer. Indeed, I think those descriptions of him are biblical, accurate, timeless, and deserve pride of-place in most churches; but, I am saying that,by itself, this description of Jesus’ work and significance misses a lot of really important stuff.

Everything depends on where you begin.

ScotMcKnight

The starting point of Christian spirituality is that we were created to work alongside our creator in the care and cultivation of our world. Then, something went wrong. However you define it- and we must always define it through some (deficient) metaphor because we lack a complete understanding of wpat it truly entails – something, somewhere, somehow,has gotten bungled up. And that is a problem. Christian spirituality, then,is about the restoration of our relationship to God, (and by extension) to our (true) selves (as god-like), to others (also god-like), and to the world (the also-creation of God).

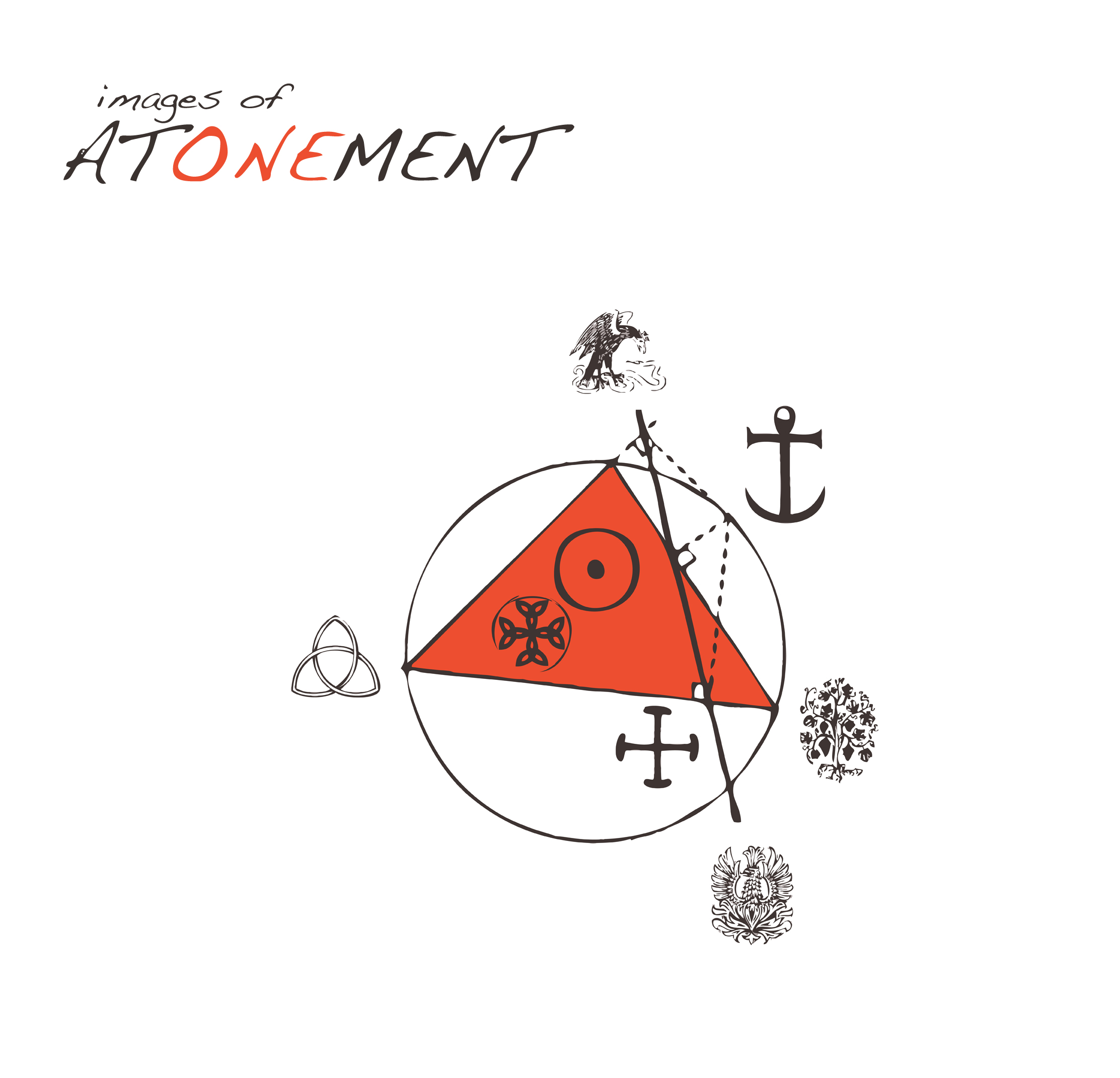

See, our big question is a question of atonement (literally, at-one-ment), how we come together with God? Now, God works through relationships. He wants us to be together with Him and these ideas are demonstrated in the biblical understanding of the covenants (Latin:co = together, vene = come).

Early on, church leaders and theologians came to understand that these covenantal stories (like Passover or the Exodus, the temple or the tabernacle) could be re-framed within a contemporary context in order to make sense to their audience. In essence, they began to use those stories as the jumping off point in their preaching/teaching – treating the stories as true (which they were) but also indicative of the ambitions of God to reach His estranged people.

For example, the benefits of the death of Christ are presented in Galatians 3.10-14 through the images like:

Christ as the representative of Israel in those whose death the covenant reaches its climax

Justification

Redemption (evoking) Exodus and exilic themes

the corollary of adoption

Substitution

Sacrifice (implied, not stated)

The promise of the Spirit

The triumph over the powers

The multiplicity of just these images ought to be sufficient (though there are many other places with many more examples in the Second Testament) to show us that there is no one right way of talking about the atonement or the interpretation of Jesus’ passion. Our earliest pastors crafted new ways to express biblical truth in their contemporary settings, making it possible for the gospel of reconciliation to be heard in ways that were easily understood. And what is it that they were trying to communicate? That restoration is possible, available, and immanent. Possible because of Jesus Christ, available now to all, and immanent to those who would willingly engage Jesus and orient themselves to him.

A biblical understanding of atonement is concerned, above all, with the restoration of mutual, undistorted, unpolluted divine/human relationship,not with the appeasing of a God angered by the misdeeds of His creatures.

Scot McKnight

Now, when we begin to talk about ‘reframing’ our understanding of faith, each of us would do well to take a moment and consider what is actually being proposed. Are we, for example, claiming that everything that has been taught up until now is irrelevant, meaningless, and trivial? By no means; quite the opposite actually. Reframing the story is not a call to abandon biblical, historical, and doctrinal atonement theology, but to think laterally and creatively about how we might ensure that this message finds traction in the world today.

We must retell our story with fresh and contemporary insight while maintaining sufficient family resemblance to our heritage within the boundaries of Christian spirituality.

AlanMann

If we want to be faithful to scripture, we must continually seek out metaphors that speak effectively to our various worlds. If we want to follow the example of the Second Testament writers then these metaphors must be at home – though never too comfortable – in our present setting. Those writers sought (as I do here) not only to be understood, but to preserve the transformational power of the gospel of Christ Jesus to reshape people, institutions, cultures, families, societies, and communal and individual desires. We need to learn the language of our world so as to undertake a translation process, thereby bringing the gospel of restoration to it in ways that make sense. We need to listen to the poets and musicians, the filmmakers and web designers, who compromise the common voice of our world and tell the story using their words and images. We need to expropriate the language of pop culture to share the narrative of God’s redemptive purpose.

Why? Because we can no longer assume that the average person on our streets has the sort of general intimacy with the history of God’s interactions with the Hebrew people that would provided the basis for understanding our metaphors of atonement as shorthand ways of referring to the biblical drama. Our metaphors are based upon the assumption of a shared encyclopedia of images…yet, people in our world today are more likely to understand Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings than they are The Day of Atonement and the Offering of the First Fruits.

We need to see ourselves as missionaries to our own culture.

We all hear them using our own languages to tell the wonderful things God has done.

Acts 2.11

fossores

Dr. David McDonald is the teaching pastor at Westwinds Community Church in Jackson, MI. The church, widely considered among the most innovative in America, has been featured on CNN.com and in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and Time Magazine.

David weaves deep theological truths with sharp social analysis and peculiar observations on pop culture. He lives in Jackson with his wife, Carmel, and their two kids. Follow him on twitter (@fossores) or online at fossores.com

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018