What explains our cultural fascination with shows like American Pickers, Pawn Stars, and Storage Wars? Is it the possibility of finding a hidden treasure? Partly. But we all know the real reason some of those “treasures” are hidden is that they don’t look like much from the outside. A seventeenth-century antique chest sometimes looks like a cheap trunk from JCPenney. A priceless-looking end table sometimes turns out to be nothing more than a Pottery Barn knock-off.

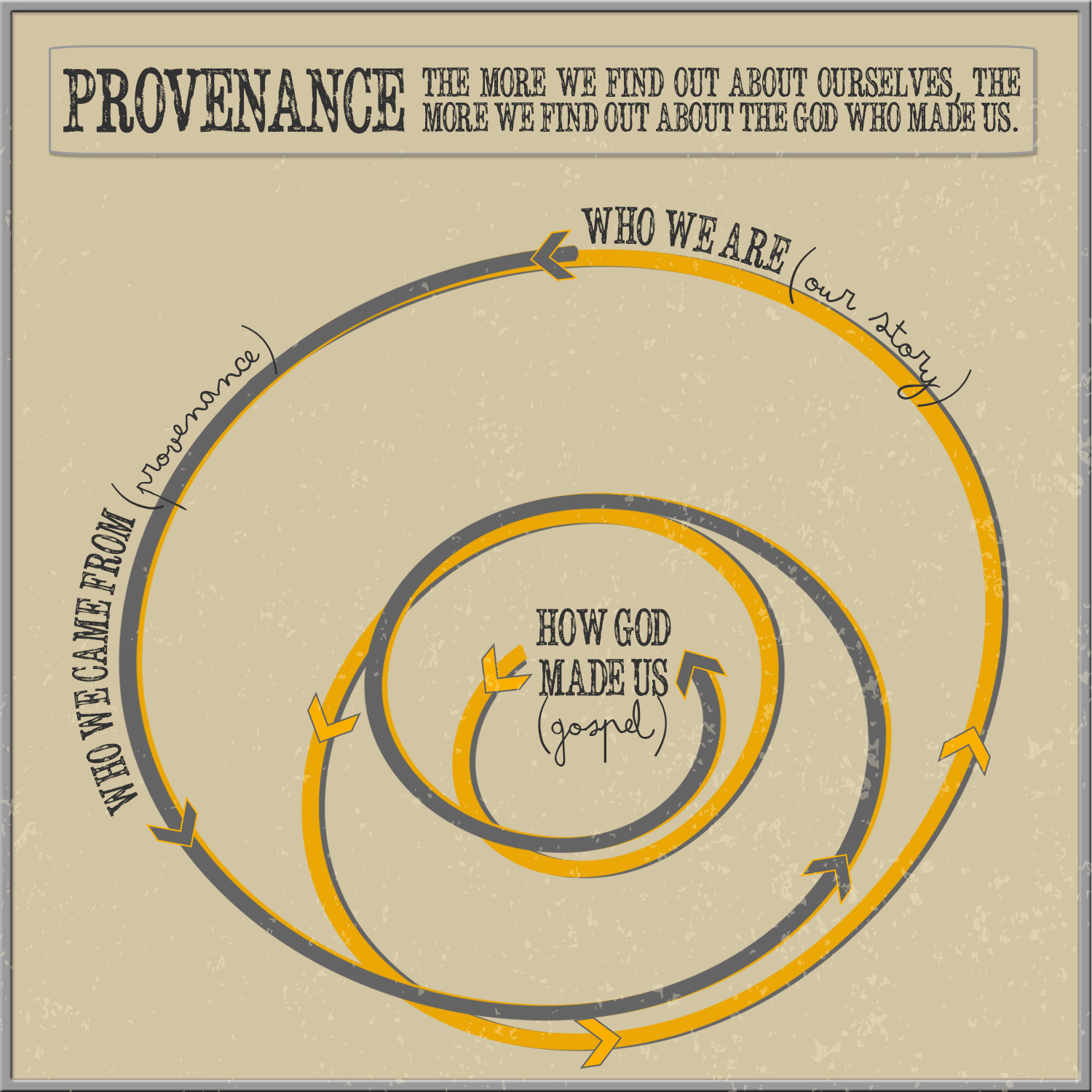

The single most important factor in defining value is provenance—the origin story.

For example, if you find an end table, and it’s several hundred years old, it’s now worth a few thousand dollars because of its age and craftsmanship. But if the same end table, from the same time period and in the same condition, is discovered to have been the dying gift of a Romanov prince to his beloved, hand-crafted as he suffered a terrible affliction, only to be delivered after his death, on the night of their planned wedding, that end table is now worth tens of thousands of dollars.

Because of its provenance.

Provenance is what allows us to charge $4 for bottled water, $35 for a block of cheese, and $15 for a craft beer. The ingredients don’t determine the value. The marketing doesn’t determine the value. The product’s value is determined by the power of its story.

We live in an experience economy where stories are currency. Our culture has lost its connection to the past, and we’re desperate to recover it. We’re rootless and aimless and, intuitively, we know this lack of connection keeps us from experiencing life the way it’s intended. Consequently, we often choose or buy experiences that make us feel like we’re part of a noble story. Gap’s (RED) campaign, for example, allows us to buy fashionable clothes and ensure that hurting children are taken care of through a portion of our spending power. Charitable giving—to churches or NGOs—allows us to participate in world-healing activity that connects us to a legacy of humanity, kindness, and redemption.

There are two kinds of gospel significance to this. First, if you have a horrible story (or no story), God invites you into his story. He adopts you (Ephesians 1.5), gives you an inheritance (Ephesians 1.11), calls you his own (1 John 3.1), promises you the protection and guidance of his Spirit (John 14.16-17), and helps you break away from the destructive components of your old life (2 Corinthians 5.17).

Second, if you are already living God’s story, delving more deeply (and more specifically) into the Scriptures will give you new energy. My parents named me David because they wanted me to have an anchor in the biblical story. When I read the stories of David I feel as though, in some small way, I am reading my stories—stories of my failure, my triumph, my redemption, my promise. From the time I can remember, my mom and dad used to tell me, “We named you David because you’re a man after God’s own heart.” (1 Samuel 13.14) In the strictest sense, they were prophesying over me, speaking a truth that could not yet be true, so as to groom and cultivate the virtue of God-heartedness in their little boy. Carmel and I have done the same with our own children. Jacob will never settle for easy answers, always wrestling with God but never letting him go (Genesis 32.22-32). Anna will see God, recognizing him when he comes (Luke 2.36-38).

Knowing our origins gives us an anchor to the past, infusing our lives with meaning. We know where we’ve come from and, by extension, we know the purest version of who we really are. We live out of our past, meaning we draw deeply on our origin story to normalize and stabilize ordinary, everyday life.

But knowing our past is rarely enough for us to live well. Our past anchors us in a good beginning, but we also need to have a sense of our destiny—our future—in order to guide and govern our lives effectively.

There are two ways of looking at the provenance of people. Ancestry is the place we come from. Legacy is what we leave behind. In the early years of our lives (including young adulthood), we tend to be more concerned with ancestry, but as time goes by and our mortality becomes more obvious, we tend to focus more on our legacy.

When we tether our past and our future, we discover our trajectory. Having a trajectory allows us to course-correct. If we sin or act contrary to our nature, it becomes a relatively easy thing to get back on course because we know what our course is. We know where it’s headed. Small deviations remain small, rather than accelerating into major deviations from our life’s meaning and purpose.

There are two ways of looking at provenance. History describes what actually happened. Mythology tells us what it means. History is the factual recounting of events. Mythology is the invisible-yet-tangible significance of those events. The United States has a history, but it also has a mythology. It is an historical fact that Abraham Lincoln abolished slavery; it is part of our mythos that this is the Land of the Free.

Jackson, Michigan has a very positive history. We’re the birthplace of one of the major American political parties, we have grown several astronauts, we have led key innovations in the field of mental health, we are the birthplace of several rock stars, news anchors, and sports heroes, and we were a key contributor to the American auto industry for decades.

However, despite our positive history, Jackson today suffers from a negative mythology. People say Jackson is dying, it’s a crummy place to live, and no one can get a job here. The old adage is “last one out of Jackson turn out the lights!”

There’s lots to be proud of, but no one’s proud.

Why?

Because our history has never been framed as mythology. We know what happened, but we haven’t figured out why it matters to us.

What we need—in society and in our families, and in our hearts—is a story ? of who we are, where we come from, and why we matter.

And that, dear friends, is the Greatest Story Ever Told.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018