Much of Christian spirituality deteriorates into posturing. When we try to sound spiritual—as though we are experts on development, discipline, and growth—we come across as vainglorious, arrogant, and egocentric.

I understand why this happens. When we grow spiritually we feel a dramatic and passionate ascent. We know we have progressed to a new level of understanding God and the movement of his Spirit. As a result, we often feel embarrassed of where we used to be spiritually, and somewhat relieved that we are no longer there, occupying—instead—a new maturity.

When we share our developmental insights with the world, it’s easy to come across as condemnatory, judgmental, and eager to shame. This ends up making us look as though we are posturing ourselves over and against everyone else. Others get the impression that we are impressed with our own spiritual maturity, and it turns them off.

Additionally, people who are posturing always sound spiritual. They sound like they’ve always known what they’re talking about, like this issue is obvious to everyone except you, like others are fools, like any disagreement with their perspective is sinful, and like there is an absolute requirement to adhere to their ideology.

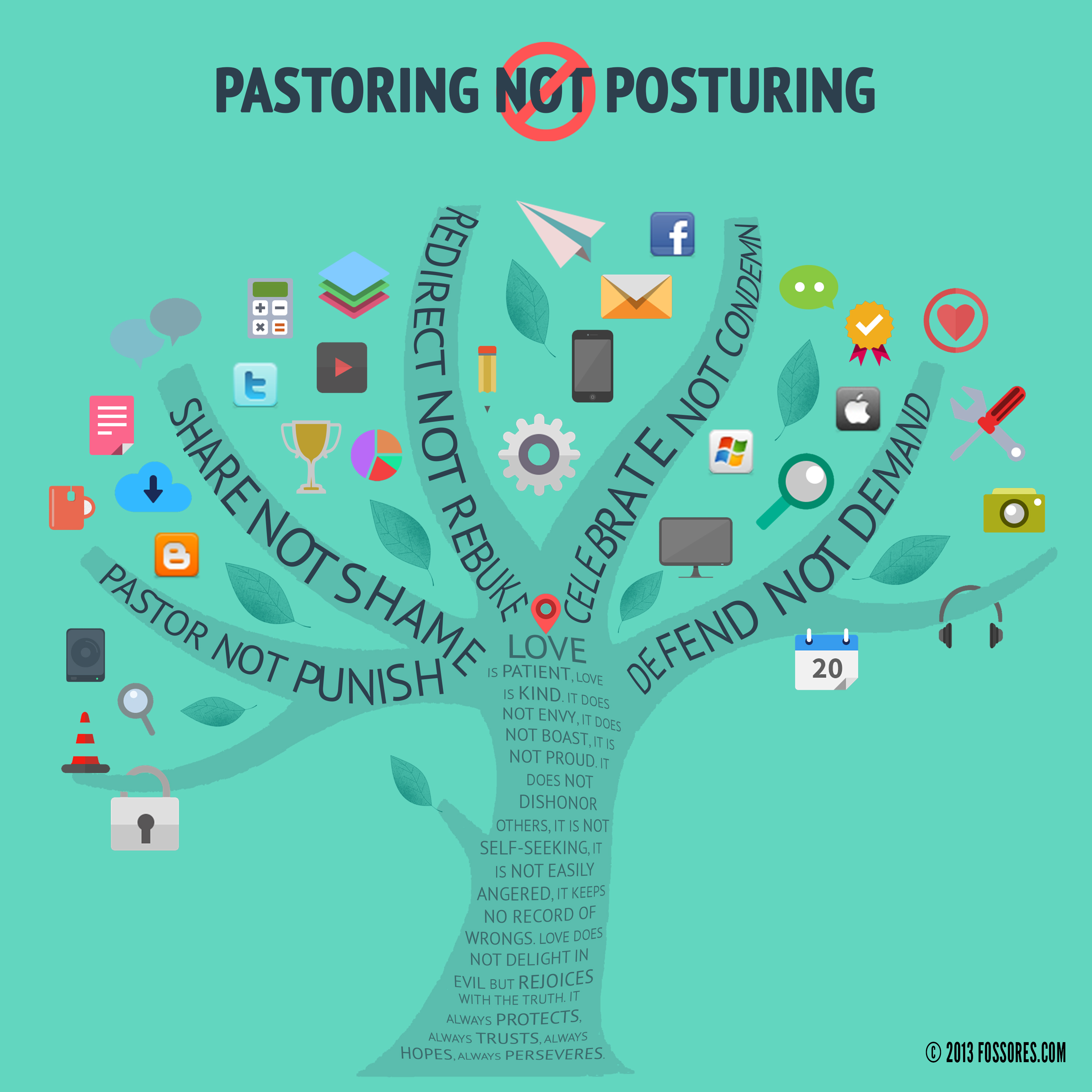

Here are my suggestions to help people grow when they make the same mistakes you once made in your youth.

1. Pastor them; do not punish them. Instead of transferring your anger and embarrassment at your own prior behaviors onto them for making the same mistakes you made, begin by acknowledging that everyone makes mistakes and everyone needs someone to lovingly lead them down a better path. That’s you.

2. Share the story of your development, not the fable of their stupidity. Do not shame other people with sarcastic rehearsals of their behavior. Instead, tell self-incriminating stories about how you once made those same mistakes and how God helped you learn not to do those things anymore.

3. Give instructions of what to do, not rebukes for what they have already done. The past is the past. The more you focus on past actions that cannot be undone, the less relational capital you have for coaching them in their future development. Spend whatever capital you have on helping them live better from here on out.

4. Celebrate the noble impulse at the root of their desire, rather than condemning the worst manifestation of their lack of discipline. No one gets into ministry because they’re an egomaniac and secretly desire to serve Satan. We get into ministry because we passionately love Jesus Christ and want to serve his church. Celebrate their desire to do everything they know how to do, with all of the resources at their disposal, to faithfully execute the mission of Christ. Assume the best. Do not condemn what sometimes shows up at their worst.

5. Defend the process, rather than demanding perfection. Ministry is challenging. No one can teach how to do ministry through a book or a seminary class or even a brief internship. We all learn how to do ministry through painful years of trial and error and much prayer. Defend people when they make mistakes, because ministry is difficult. Give them grace. Do not demand that they become as perfectly formed as you are now, 20 years ahead of your own developmental timetable. No one is as competent at 20 as they will be at 40. No one is as spiritually mature at 26 as they will be at 62. No one has the breadth of understanding, education, and experience in the first half of their ministry as they will undoubtedly attain by the end of their ministry. Our job is to ensure that they do not quit because they have been bone-crushingly discouraged by our unrealistic expectations.

We all need to think back to the spiritual trainers who helped form us into Christian ministers. Some of us had good trainers and some did not. But we all know what kind of mentor we wish we’d had when we first started out. We now have the opportunity to be the leaders we needed when we first recognized our need to be led.

Let’s be those guys, for the new guys.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018