I nearly died Saturday under the ice.

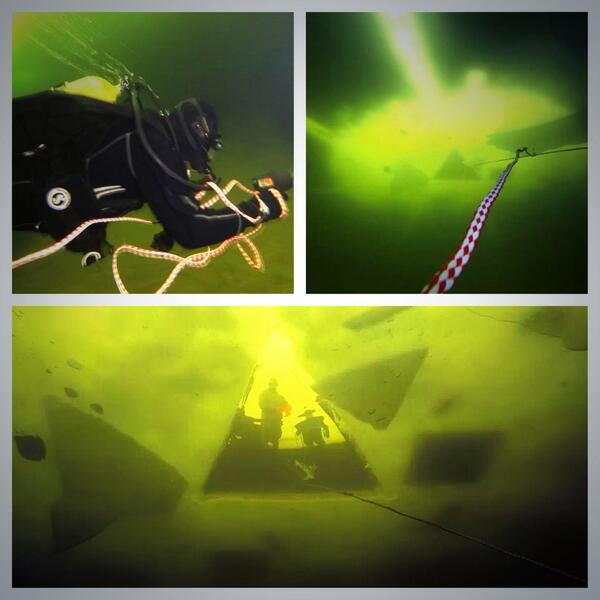

I’ve been scuba diving for four years. I’ve got 125+ dives in many different locations. I’ve dove in warm water, cold water, caves, shipwrecks, reefs, through reedy kelp, and in zero visibility. I have my Nitrox certification, my Advanced Open Water certification, my deep diver ticket, my wreck diver ticket, and—as of this past weekend—my ice diver ticket, too.

I’m not an expert diver, but I’m not a novice either.

In hindsight, I wasn’t in as much danger as I thought. There were eight divemasters present, a medical trailer, and a rescue dive team on standby. I was also diving with my buddy Jeff, who is an experienced master diver, and I was wearing a tether. I had plenty of oxygen remaining in my tank and was less than two feet under the water.

To be fair, there was no way I was actually going to lose my life Saturday. But I thought I was, and that’s the point.

Many things can go wrong when you dive. Your fins can tear, your mask might not seal properly, you might get a freeflow in your regulator or have a small leak in your first stage, you might need more (or less) weight, and it’s always possible to get disoriented. The goal is to solve every problem under water so you avoid emergency ascent and decompression sickness. Or drowning. You train for those scenarios, so when they happen you don’t panic.

I panicked.

It was only 4 degrees above the ice. We’d spent several hours cutting the hole and preparing the dive site. I didn’t have waterproof boots, so I couldn’t feel my toes when I went to suit up for the dive. I also had a head cold, which made breathing through my nose laborious.

The most important thing to keep in mind when ice diving is that your equipment is likely to malfunction in the cold. You’ve got to get your regulator in your mouth underwater without breathing on it first, and you’ve got to keep your head under the water to ensure the regulator doesn’t ice up and malfunction.

I was wearing a new drysuit with several additional layers of clothing underneath. As a result, I didn’t have the proper weight to be able to descend into the lake. Additionally, the deflator on my drysuit wasn’t responding in the cold which meant I had air trapped in the suit that made me extra buoyant and I wasn’t able to get rid of it.

I jumped in and forcibly trapped myself under the ice to gain my composure and regulate my buoyancy. After several minutes, I had to resurface in order to add weight to my dive gear.

Did I mention that resurfacing during an ice dive is super-lightning bad?

Fortunately I was able to take my regulator out and hold it under water so it wouldn’t freeze. The surface team clipped extra weight onto my gear, and I tried again.

And again.

And again.

It took three trips to the surface before I was weighted properly.

(Did I mention that resurfacing during an ice dive is super-lightning bad?)

Little did I know, the extra weight impeded my inflator. So I sank straight to the bottom of Lime Lake and buried myself face down in the muck. Thankfully it’s only about 25 feet deep, and my friend Jeff was able to swim over and rearrange the weights so I could put some air in my drysuit.

We began our dive nearly ten minutes after first entering the water. It lasted about 38 minutes, and the only real hiccup I had was with my mask. It wasn’t sealing properly, and water kept leaking in. No big deal. There’s an easy way to clear the mask, but I had to employ the technique about every twenty seconds. Typically, I’d just surface and fix the problem but that doesn’t work under the ice. Again, no big deal. The only real danger with water in your mask is that your brain tends to get confused when the water level reaches your iris. The brain thinks you’re drowning, regardless of whether you’re getting air. I’ve had all that happen before, and it’s really not something to worry about.

When you do any penetration diving, such as shipwrecks, caves, or ice, you always hold onto a line. A surface team signals you through a series of jerks and tugs, and you can alert them in a similar manner. In ice diving, you and your dive buddy are both tethered to the same line to ensure you don’t wander off by yourself. It makes things a little tangly, but also much safer.

Most of the time.

Toward the end of our dive, Jeff and I began passing over a series of underwater ridges. Lime Lake has some uber-cool rock formations that make it feel like you’re flying over the Himalayas, so diving around those spots is almost my favorite portion of the dive. But my mask was still acting up. And it was getting worse.

Jeff and I ascended to about 10 feet in order to get over one particularly tall ridge. That’s when the problems began.

When you ascend, the gas molecules in your drysuit expand, causing you to ascend more quickly than you’d like. When we went over the ridge, my mask flooded. As I reached up to clear my mask, the air in my suit expanded, shooting me to the surface. I cracked my head on the ice. It spun me around, wrapping my arms against my chest and limiting my mobility. I still needed to deflate my drysuit and my mask was 75% full of water.

I was trapped against the surface of the ice and I couldn’t move.

Then I couldn’t breathe.

I had lots of oxygen, but my brain kept telling my body it was drowning. I couldn’t get my lungs to obey. No matter what thoughts I consciously directed to my air passages, I kept breathing through my nose. I inhaled massive amounts of water, spitting it out through my regulator. My panic intensified and I began to shake. I wasn’t sure which problem to solve first: flooded mask, over-filled drysuit, trapped arms. As a result, I flip-flopped between spastic attempts at each, never really giving effort to any one thing.

They say, at the moment of your death, your life flashes before your eyes. I remember feeling ripped off that mine did not.

I imagined dying and seeing heaven across a field of mint and grass, knee-high, like swaying long-weave carpet. I was just a thing moving through it. I imagined heaven as a city on a hill, and I climbed a long way to get there. And when I did, I saw Randy Shafer reading books in a library, relaxing in a leather chair, and Mema sitting outside with Papa at a chess table drinking tea.

And then, with just these glimpses, heaven is gone. And everything ends. And begins again. And because of what I’ve seen I can’t swear. I can’t lust. I can’t hate. Having seen the reality I’ve only suspected but never found, I don’t even want to come close because the very thought of disobedience shatters my spirit.

I thought briefly about my work—my books, my unfinished projects, my efforts at Westwinds and George Fox Seminary—and wondered why I didn’t care more about it in that moment. I remember thinking: Nope, that stuff’s neat but it doesn’t count right now. And then I remember being flooded with an incredible sadness.

I was going to die and only two things mattered.

I was overcome with the knowledge that Jacob and Anna would grow up without a father. I imagined all the people who would try and step in—my friends, my father, my father-in-law, my brothers, their teachers—and, good as they all are, none of those people have the privilege of being Father to Jacob and Anna. Only I can tell them how proud they make me. I’ve told them before, but they don’t know how magnificent they are.

I also felt sad for a handful of very specific people. I see them in my mind, still, and I’m not sure why these people are the ones who came to me. The gallery seems random, but I remember thinking: How will they learn of the goodness of God now that I’m gone?

Isn’t that strange? These are people I know but not well. They’re acquaintances at best. I like them, but I certainly don’t know them well enough to speak about my spiritual beliefs, let alone theirs. But, as I was dying, I saw their faces and my heart split thinking of something I have to say.

I thought I was going to die. I remember telling myself the only real danger I was in resulted from panic. I told myself: Don’t panic. But what came through my head was: DontPanicDontPanicOhMyGodImPanickingThisIsPanicImScrewed.

I was trapped, blind, and couldn’t breathe.

That’s when Jeff, my dive partner, came to check on me. I remember seeing him through watery lenses and noticing his eyes were saucer-wide. I reached out and grabbed his shoulder, still struggling for air. He removed my hand so he could hold it with his. He shook once, firmly, and I began to calm down. I cleared my mask. Jeff helped with the rope. I was able to get the excess air out of my suit, and then Jeff motioned that we return to the entry point.

I appreciate the way Jeff handled the situation afterwards. He played it down like it was no big deal. His only comment was, “You did good. We fixed our sh*t underwater and now we’re dry. That’s how it’s supposed to go.”

I’d love to say my terror ended with getting out of the water, but it was just the beginning. I had to reenter the water Sunday afternoon in order to complete my ice diving certification.

Alone.

I spent Saturday evening in near catatonia. I woke up several times in the night in hot sweats, deeply troubled.

I couldn’t figure out why, precisely.

I’ve examined my thoughts, and I can honestly say I wasn’t afraid of dying. It wasn’t death that bothered me. I was saddened at the thought of a world without me, at the hurt those I love would experience with my passing. Jvo can hardly keep from crying on a Tuesday—what’s he going to do at my funeral? I imagined people crying, but I was unable to comfort them. I imagined people looking for answers, but I couldn’t counsel them. I imagined people finding out how I died, but I couldn’t reassure them.

I didn’t how to process the bitter ache I was feeling, so I wrote letters. I wrote one to Carmel (“I never regretted one moment.”), and to Jacob (“When I first held you, everything changed. I felt like I was being born, too.”), and to Anna (“You are perfect, the daughter of a King.”). I updated my will. I wrote letters to the people who had flashed into my mind, telling them of God. I sang. I prayed. I sobbed in the bathroom, hiding in the shower and covering my face with a hand towel.

I had one more dive to do. I knew I had to do it. I knew I wasn’t in any real danger the last time and that I wouldn’t be in any real danger this time, either. But that didn’t keep me from watching my own funeral in my head, as though I was a ghost, hovering above the Westwinds’ auditorium.

I dove with my regular dive buddy and friend, Jason. Our abilities are comparable, and Jason knew I had struggled the day before. I had told him some of what had happened, though not in great detail.

I was late getting to the lake after church Sunday. The surface team knew I was nervous and got me back in the water as quickly as possible since that’s the best way to dispel jittery nerves.

The final portion of ice diving certification is rescue and recovery. You have to learn how to find a lost diver under the ice and bring the diver back safely. You also have to pretend to be a lost diver under the ice so another diver can come and rescue you.

Jason was the rescue diver on the first dive, and I was the lost diver. Less than 15 hours after my near-death experience I was back under the ice. My mask began leaking immediately. I was alone. It was dark. It took Jason ten minutes to find me. When it was my turn, I found him after twelve.

You might wonder: Why did you go back?

I knew if I didn’t return I would carry that fear until the next time I dove. The longer I waited, the more that fear would infect me, making me skittish, small, and suspicious of every unknown. I knew I would keep diving, but if I didn’t get my confidence back then, the next time something went wrong I might recall the panic from under the ice and have both events compound into an irrecoverable disaster.

I also went back for my children, so Jake and Anna see what it’s like to face fears. This might seem foolish. If I died, it would only teach them that their father was a cavalier jackass who threw his life away on a hobby. But, beneath all my fears about the dive, I put my trust in the Lord of the Waters.

That’s an old term for God from the prophets and psalms. The water was a chaotic presence in the Ancient Near East, typically associated with wayward and demonic powers. Calling God “Lord of the Waters” meant acknowledging his supremacy over chaos, malevolence, and fear.

I went back under the ice in the presence of God, Lord of the Waters, and of me, also.

The dive was fabulous.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018