In his book Free of Charge, theologian Miroslav Volf shares a funny thought experiment. He tells us to imagine we’ve been invited to an all-expenses-paid ski holiday, flown to a private hill on a private jet and treated to the most extravagant delicacies for ten days. Our meals are specially prepared. Our tours are professionally guided. Our instruction is from Olympic coaches. Our company is movie stars and ambassadors. At the end, when we go to thank our host for his generosity, Volf tells us to imagine that our host responds by saying, “It’s not a problem. I like to give a little help to the poor when I can.”

Volf wants to know: how would that response make us feel? Ashamed? Belittled? Of course! This generosity is a kind of back-handed slap, a sneer that ends up demeaning us and casts a pall over the whole holiday. Instead, wouldn’t it be better for the host to have responded with something like, “It’s not a problem. God has been generous with me, and it gives me great joy to share what I have with others.”

The biggest obstacle to generosity is not your money but your mind.

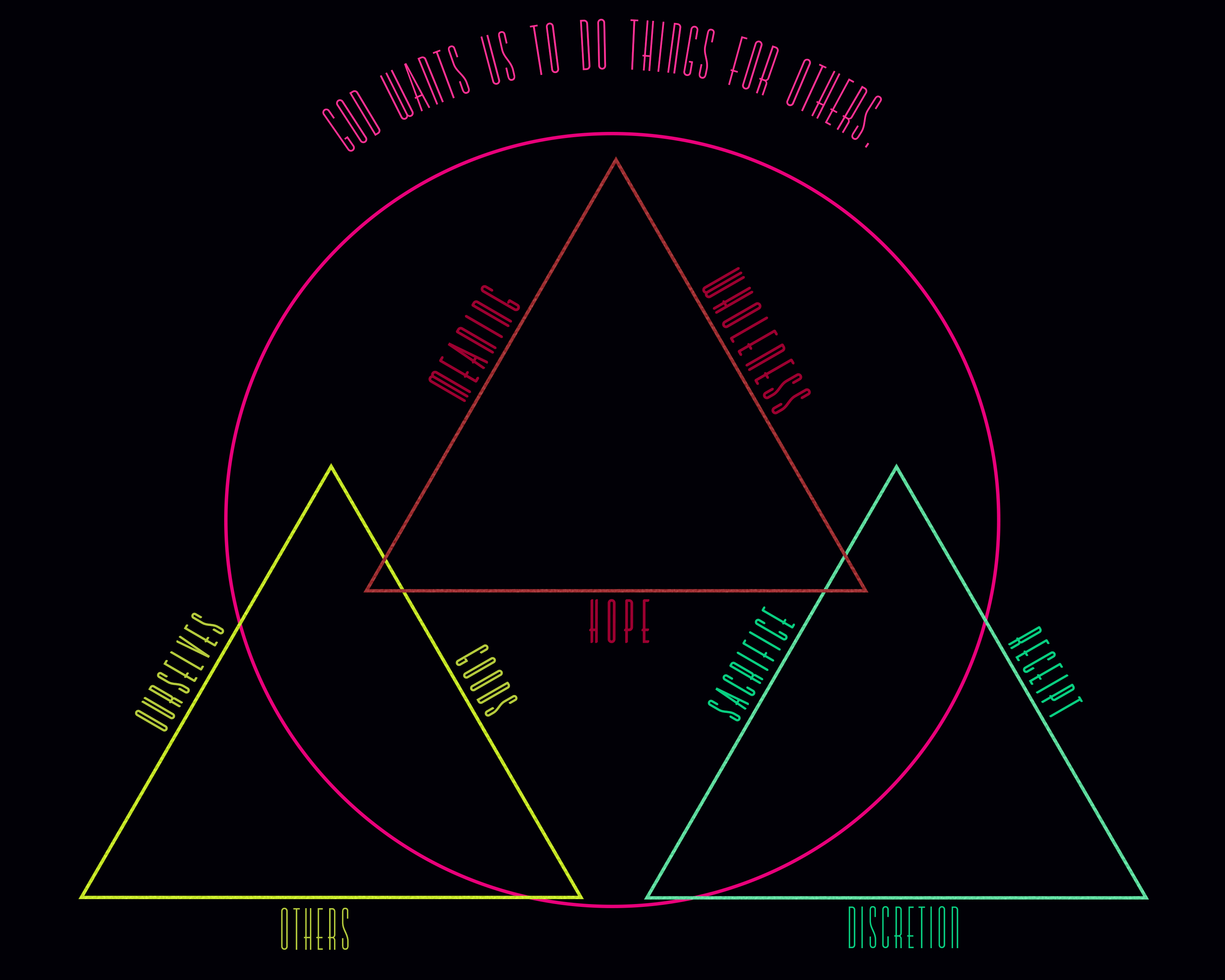

That, however, requires we change our perspective on others, on ourselves, and on our goods.

We can no longer see others as our competition. “They” are not stealing our jobs. “They” are not the problem with our economy. On the contrary, we are here to bless “them.”

“Don’t be selfish; don’t try to impress others. Be humble, thinking of others as better than yourselves. Don’t look out only for your own interests, but take an interest in others, too.” Philippians 2.3-4

“They” are meant to benefit from us.

This is tricky, because it sometimes means that our desire to give will collide with someone else’s desire to get, and we will feel like we are enabling them or like our noble efforts are futile.

I understand this kind of despair, and there’s much we could say about it (see my work on Justice and Charity, or Heart of Gold, for example). But, for now, suffice it to say that our generosity is more transformationally effective than our problem-solving; meaning, the more we try to fix others, the more they resist being changed. But the more we bless others, the more contagious our generosity becomes.

The other change we need to see is a change in ourselves. We’ve got to stop thinking about how much we have (or don’t have), and train ourselves instead to think of how little we need. When our wants and needs become inseparable, we lose our ability to enjoy simple gifts.

I spoke about this briefly in a previous post, but—at the risk of beating a dead horse—I want to highlight something we taught our children this year in preparation for Christmas. When our kids put together their 2013 Christmas lists, the grand total value of all requests was just under $10,000.

That’s, ahem, more than we planned to spend.

So we told Jake and Anna we weren’t going to do Christmas lists this year. We were afraid if they kept their lists, the only possible outcome on Christmas Day would be disappointment. No matter what they got, it wouldn’t be all they wanted.

Instead, we sat down as a family and planned out how Christmas would go. We dreamed up new ideas and discarded some of the old ones (NOT the rule about Christmas officially beginning AFTER 8am, however…Daddy was firm on that one!).

I was worried the kids would be jerks about the whole thing, but they were fantastic. I felt super-proud.

Now, we’ll see how Christmas morning actually goes this year; but, in the meantime, I’m glad we had that talk. It helped my kids realize that their expectations had way outstripped reality. Instead, my kids have no idea what they’re getting and are already thinking about how they’re going to enjoy whatever it is, thereby giving the gift to their parents of gratitude, laughter, and enthusiasm.

Which is as it should be.

The last mental change we need involves no longer thinking about our goods as “things we’ve earned.”

Everything we have is a gift, whether we earned it or not. Most of us even have things we’ve “earned” but cannot enjoy because whenever we get something “with our hard-earned money” we cannot help but evaluate it.

Was it worth it?

How come it’s not as cool as I thought it would be?

Hey—I paid for this, I want it to work!

But when something is a gift, we are free to enjoy it for what it is instead of appraising what it is not.

Case in point: I recently bought a hot tub from a friend. It was 20 years old, but I paid almost nothing for it, and shortly after I set it up at my home it broke. It was too expensive to fix, but I don’t regret buying it. I loved having a hot tub, even an old pink one. It was a luxury I never thought I would get to enjoy. I felt tremendously blessed during the time I had it and I still feel happy and grateful and thankful to God for the few times I was wet and warm in Michigan’s winter.

The person who sold me the tub was worried I’d be upset or feel ripped off.

But why?

The tub was 20 years old. Of course it was going to break! The sum I paid for it was laughable—less than it was worth—so why should I complain? I was warned in advance by Joel Ladwig, who runs The Great Soak Hot Tub Company, that old hot tubs invariably explode. When mine did, Joel helped me find a (newer) used one at a fantastic price, and now I feel super happy about that, too.

My point is this: gratitude enables pleasure. When everything is a gift, you can enjoy it regardless of what you paid. But purchase and security are not gifts. They are contracts. And when you perceive your contract to have been broken, the only possible response is anger.

But life is too short for anger.

We are to become people of the gift, both freely giving and freely receiving.

“Freely you have received; freely give.” Matthew 10.8b

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018