There’s nothing so crazy as church-weirdo crazy.

A few years back, a young angry white kid accosted me in our lobby decrying the irresponsible use of church resources on a building. He claimed that if we were serious about following Jesus, we should sell our building and give all the money to the poor. He told me Christians never owned property until Constantine imperialized the faith and that Jesus would never set foot in a false temple.

When I tried to respond to this caustic collegiate by gently reminding him Christians were buying and constructing buildings within forty years after the resurrection; that one of the main reasons they hadn’t done it earlier was due to their regular welcome in Jewish synagogues; and that Jesus did, in fact, visit many houses of worship, he stormed off, claiming I didn’t know what I was talking about.

Do I?

Does he?

How can you tell which of us had the right answer?

This leads to an even bigger question: How do you find answers you can actually trust?

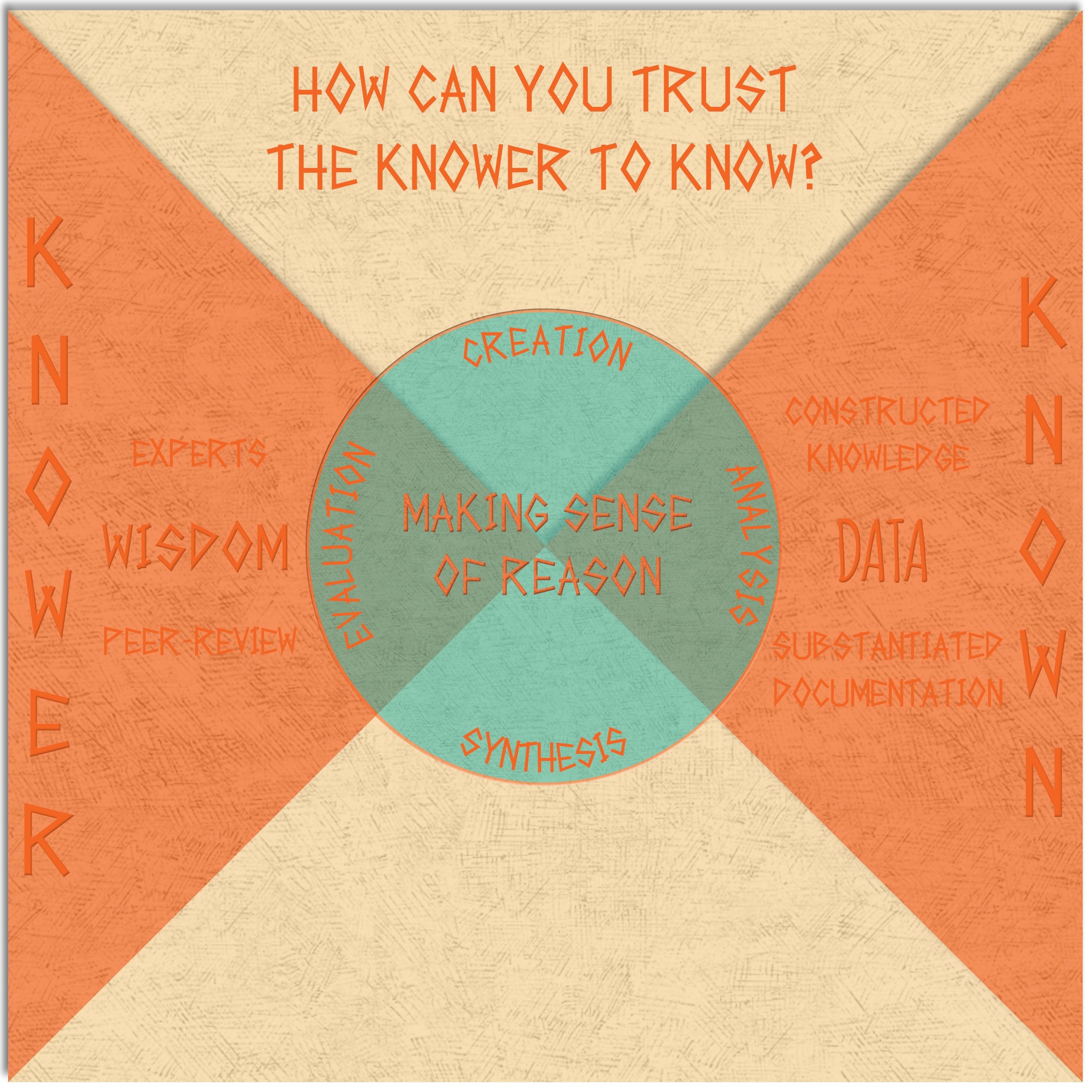

And then, how can you trust the knower to know?

The knower is the person who claims to have the answers you’re looking for. The ultimate test of their knowledge is peer review. If you’re involved in any kind of discipline, and the established names in that field recognize you as a voice worth considering based on the fact that your ideas have been substantiated and have merit, then congrats—you’re an expert. That means when you speak about your area of specialization, people should listen. It also means you can have confidence when you make decisions within your field because—even if you don’t know 100% of what you need to know—you know how to find the remaining information required.

On the flip side, if you’re looking for answers on a given topic, find a respected voice in that field. Don’t consult physicians about vehicular mechanics. They might be experts, but not in automobiles. The learning and expertise they’ve cultivated is in a completely different arena, and even though they may be intelligent, their opinions do not make them experts in every field.

As to the subject matter itself—the vast array of facts and data available on the web, or in books, or through schools—it’s also important to adjudicate the known. The known is the constructed knowledge within any given field. It’s the history of medical science, or the long record of Christian theology. Credible knowledge has been substantiated by research, documentation, and careful analysis.

To develop a basic framework for how to know something is true, it’s important to know you can trust the knower to know, even if the knower is you.

Make sure all relevant data is analyzed, then take that data and synthesize it with your own thoughts and experiences, then evaluate your presuppositions and early conclusions based on the wisdom of the experts, and then create a solution to your “knowledge problem.”

Let me give you an example. Last year I was trying to articulate the best guidelines for “how to work Christian-ly.” I’m often asked how people are supposed to “live out their faith at work” and I struggle with giving good, succinct answers. I’m not sure there’s an externally observable way to be Christian at work. You might say, “Christians are ethical and cheerful and responsible” but a simple counterargument acknowledges that Buddhists are, also.

I began to read widely on the topic of contextualization and cultural engagement in Christian theology. I realize that probably sounds as exciting as watching ants fingerpaint, but it’s actually a widely accepted subset of Christian thinking. So, to start, I analyzed existing thought.

Then I began to bring some of my own thoughts and ruminations on the topic (from years of journaling and reflection) into the conversation with the historical data. I noted similarities and differences, shored up some weaknesses in my own thinking and looked for intelligent objections to overly simplified conclusions. I synthesized my work with the established work in the field.

At this point in my career, I can safely be considered a “knower” in the field of Christian theology and practice; but, I still wanted to run some of my synthesized thoughts past a few friends and colleagues so they could evaluate my conclusions. This stage is critical because it allows other people to punch holes in your ideas and helps you find blind spots in your argument. I subjected my work to evaluation.

Finally, I felt confident that I really do know a few important things about how to function as a healthy Christian person at work. I now feel qualified to teach these things to others and am well-equipped to defend my thinking from reasonable, credible, historical data. Some of my thinking is original, which simply means I have a unique contribution to add to a historical conversation; but the point is that my thinking stands in line with that conversation, even when I disagree with it, rather than being some free-flowing opinions of mine on something I’ve never studied.

In sum, you can trust the knower to know based on their analysis of existing thought, their synthesis with the established work in the field, and review of their work by peers.

Oh—and that angry white kid? Last I heard he was making the rounds of all the churches in Jackson, still spouting about how wrong we all are. That’s sad, but not unexpected. He’s probably too hung up on finding false temples to recognize good churches when he visits anyway.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018