Many contemporary Christians point to the “early church” as a community of leaderless, purposefully poor communists who found their true identities in home-cooked meals and quiet times of prayer. But there was never just one “early church,” nor was it ever harmoniously and homogenously enjoyed.

Case in point, the letters in the Second Testament were written to many different churches and church leaders, each facing tremendously complex situations that required strong leadership, guidance, and accountability. The Corinthian church wrestled with different issues than the Galatians, and—as the seven letters in Revelation make clear—they were not the only ones who required supervision.

Within about 50 years of Christ’s resurrection, Christians were expelled from synagogues (in 85 AD) and began to construct their own facilities, pay pastors, and submit to hierarchical and non-local authority. In Acts, Christians gathered in the synagogues and in their homes. By 100 AD, Christians gathered in their own church buildings and in their homes. Regardless of who owned the big building, there has been a pretty consistent pattern of “big group” and “small group” meetings since the First Testament.

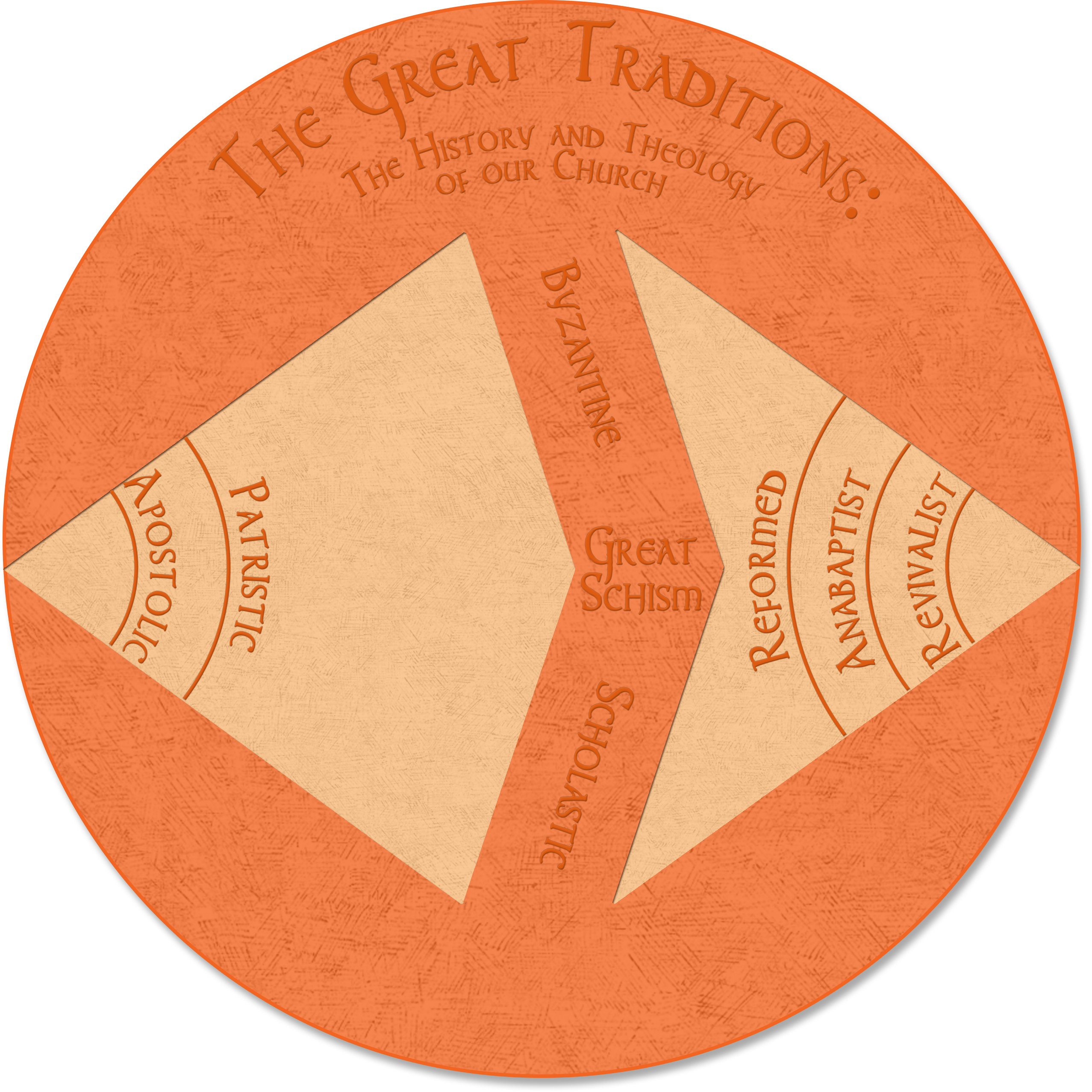

Rather than lobotomizing our Christian heritage back to the book of Acts, I think we’re wiser to learn that every great epoch in church history has been dramatically different, and those differences are good. We learn from difference. The essence of creativity is the juxtaposition of difference.

As you read through the following, think about which of these movements you relate to most closely.

The first major period in church history is known as the Patristic period. This was the era of those we know now as church fathers—men such as Irenaeus, Athanasius, Origen, and Augustine—and focused on apologetics and tradition. This is also when several foundational doctrines were established, including the doctrine of the Trinity. If you’ve always fantasized about living in the desert spouting aphorisms, these are your guys.

The second period is Byzantine. This is when the Eastern church began—Eastern Orthodox, African, etc., honing in on the ideas of hesychasm (stillness and silence) and theosis (coming into union with God). Church fathers in this movement were St. Symeon and Isaac the Syrian (or Isaac of Ninevah). If you geek out on mysticism, Obi Wan Kenobi, or Shaolin Temple Kung Fu, you might read more about them.

Next is the Scholastic movement. This is when the Western church emerged, with leaders like Thomas Aquinas and Thomas More, who put emphasis on knowledge and textbook theology. This era forms the background for much of the church in the Westernized world. If you love to win arguments, defend the truth against angry idiots, and study ‘cause it’s fun, you should dive in deeper here.

The Protestant Reformation soon followed, with Martin Luther’s famous Ninety-Five Theses and the ultimate split from the Catholic church. John Calvin is another of the foundational leaders of this period. The Reformers were passionate, ambitious leaders who sacrificed personal comfort for the sake of the gospel.

The Anabaptist movement started in Europe. Menno Simons was a key leader in this movement in the 1500s. Anabaptists stressed nonviolence and nonconformity to the world. The Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites are all modern-day Anabaptists. If you’re concerned with advocacy, justice, and protest, then these are your new best friends. If you pride yourself on exhaustion, endurance, and grit, these are the guys for you.

The Revivalists arose in Protestant Europe and in America (The Great Awakening), with such leaders as Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield. This movement emphasized the power and validity of personal experiences with God, as opposed to the textbook theology of the scholastics. If you’re constantly looking for your next dose of the Holy Ghost, you should consider reading these guys devotionally. They make our charismaniacs look comatose.

My best advice is this: learn to accept differences and honor them. God’s kingdom isn’t one color, and his church doesn’t have one style. There’s a lot of room for godliness on all sides of tradition, theology, experience, and prayer.

You show me yours, and I’ll show you mine.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018