Since 2008 I have written in excess of two million words, comprising fifty-six books, thirteen white papers, and hundreds of explanatory diagrams translating the best historical theology into the language of ordinary, everyday people. The Teaching Atlas project began as a means of distributing my spiritual impressions to congregants at Westwinds Community Church (westwinds.org), but over the years I have also been able to raise money for local charities, highlight notable people within our community, and dabble in speculative theology—even fictionalizing the process of missionary work in Atlantis.

I have written three books this year, including The Handbook for Hellfighters (a training manual for ecclesial ministry) and The Church Survival Guide (a contemporary “rhyme” to the Rule of St. Benedict). In 118 hours, after seven years of research and three weeks of preparation, I wrote The Garden-City Epistles—56,487 words in a daily devotional on human becoming.

Here’s what I’ve learned:

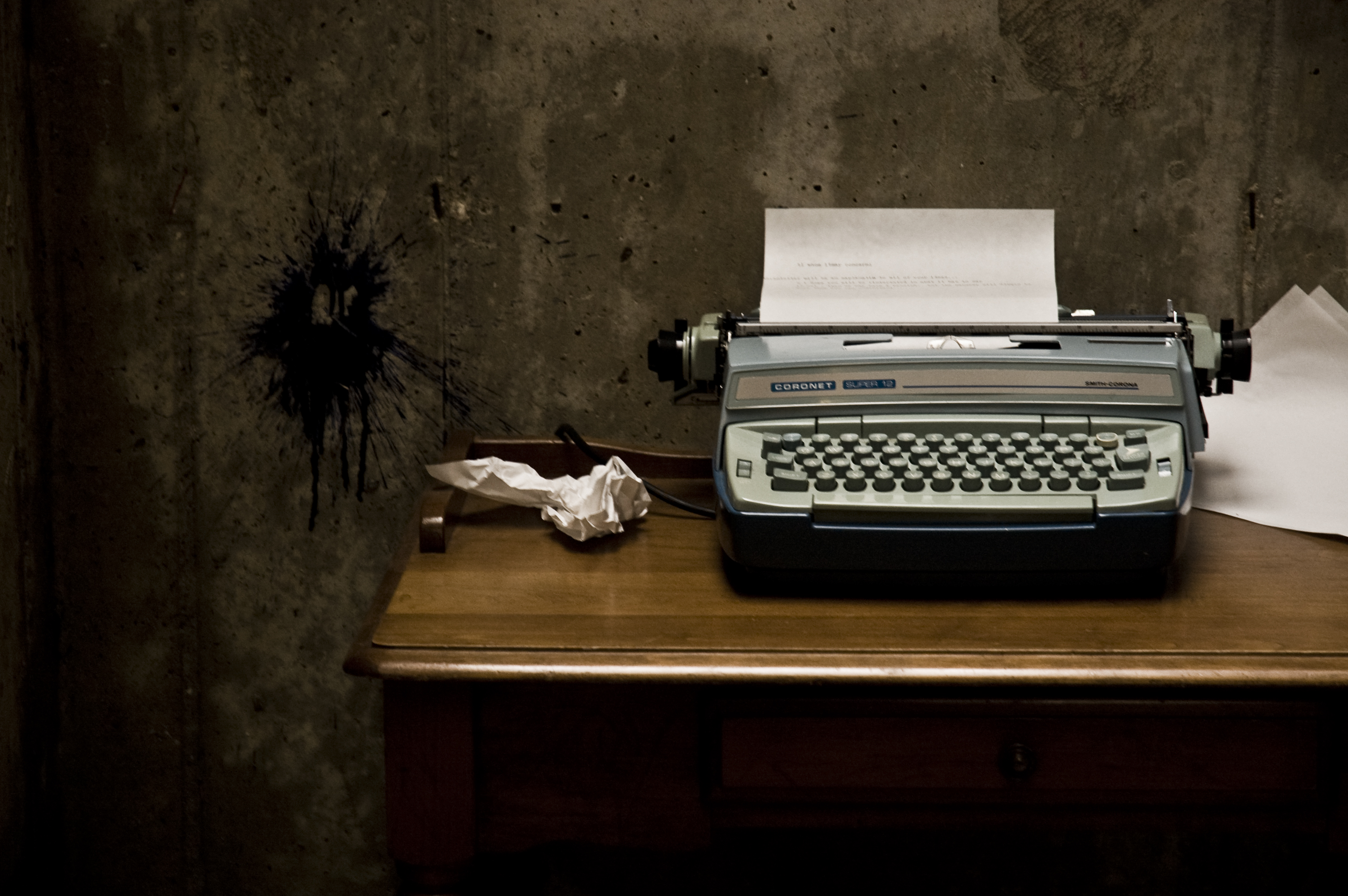

Passion will get you started, but discipline will see you through. Theology is fascinating stuff, but it’s a lot of work to explain, to develop, and to substantiate. The only way to complete such a task is to set a schedule, write like mad, and never stop, even if you despair. Get your first draft finished before you pay attention to your feelings, since—in the early stages—most of your feelings will be negative.

That’s not just true for continued writing, but for getting started as well. The first worst words will rarely be your best, and the fear of bad writing often keeps us from the initial click on the keys. But writing is like jumping into a cold lake: you squirm less once you’re all in.

Once my articulate brilliance rushes through my mind and onto the screen, I know I’m in trouble. The more the writing flows in the first draft, the more you’ll have to trim it back during revisions. I don’t try to interrupt the flow, but I know the next twenty-four hours will likely involve head-shaking, smirking, and self-recrimination. Easy means effortless, and good writing is never easy any more than good abs result from doughnuts and naps in the afternoon.

What interests you is only interesting to the audience if there’s a payoff. Most people don’t spend their afternoons reading 4th century African theology. In order for my writing to gain traction, I have to answer the all-important question, “So what?” The book, after all, is for the audience. I’m not writing to exercise demons, but to share about how you, too, can get your demons looking great in a bikini by summer.

Your work is not the best work on any topic, but it is yours. I’ll never be on a shelf with Meister Eckhart, Athanasius, or Jacques Ellul, but most people don’t have theology on their shelves anyway. My mission isn’t to compete with the greats, but to translate them for everyday use. The translation is mine—my voice, my take, my slant—and it’s the only thing I’ve got to offer.

Not only has publishing changed, but reading has, too. You need shorter chapters, earlier payoffs, and more memorable axioms to keep people turning the page. Every story is comprised of smaller tales; every tome is a hundred pamphlets; every dissertation is a dozen arguments working together to make one point. When we forget this, people put down our work and are either dismissive or angry that they wasted ten bucks.

That’s right—ten bucks. Our therapist-employing, dotage-initiating, profanity-inventing work of desperate passion isn’t worth nine cents an hour. And how do I know this? Because, as my friends are fond of saying, “There isn’t another pastor on the planet that puts out like you do,” and this is the first time you’re seeing my name.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018