I do most of my sinning on Sunday mornings. Especially between the hours of 8am and 1pm. That’s ironic, given that I’m a pastor and most Sunday mornings I spend preaching from the Bible, but it’s true. If you’ve been to Westwinds you may think that the sins I’m referring to are “boo-boos” (off color jokes, accidental double-entendres, sarcastic remarks, etc). But those aren’t the really nasty business of sin; they’re just the immature icing on the cupcake of depravity.

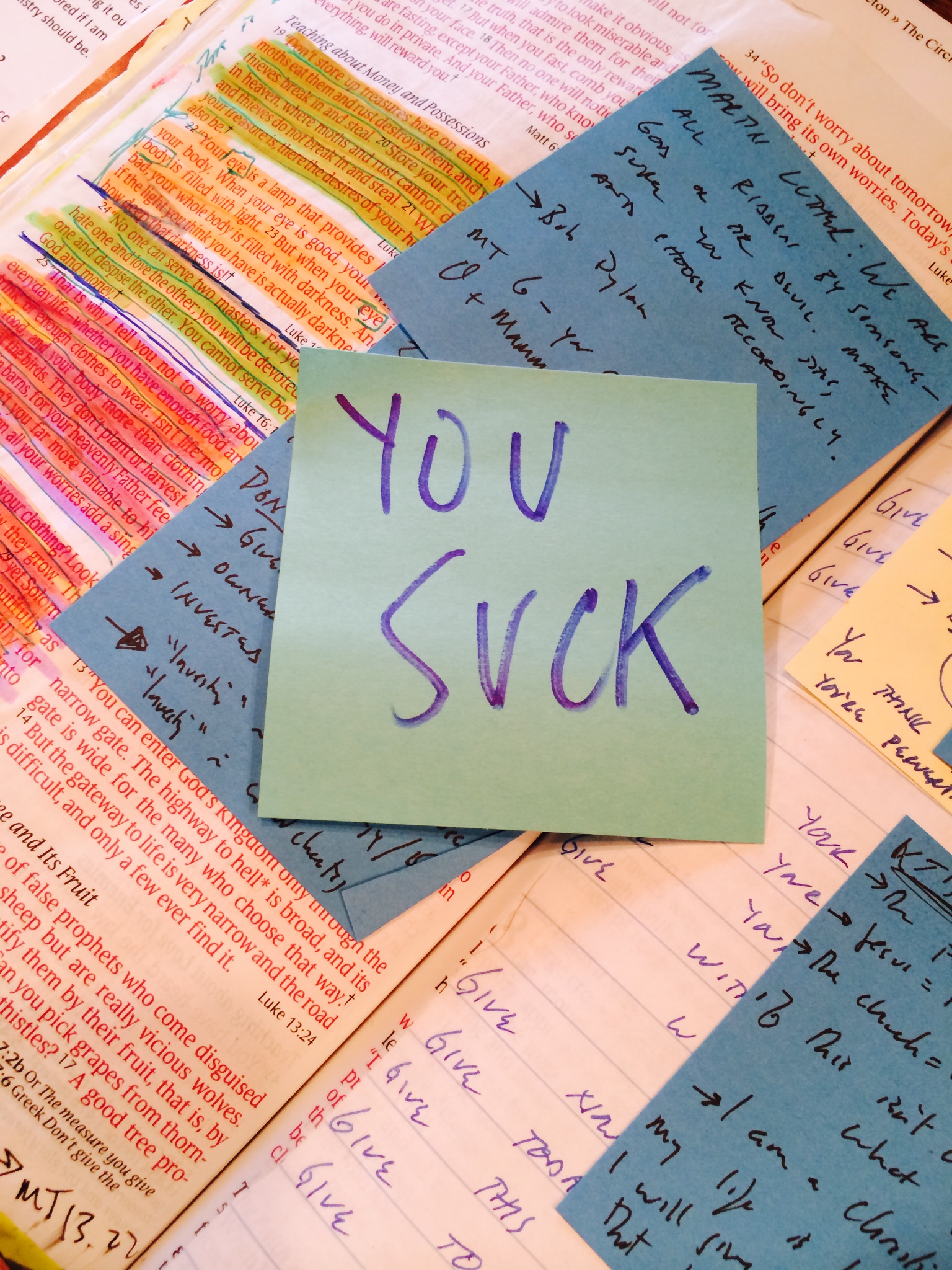

No—the truth is that my mind is a festival of sin, especially while preaching against it. I can’t seem to stop from making assumptions about the people gathered in church, or arguing against people I imagine don’t totally agree with me, or getting irked by people’s facial expressions. My sins are mental, and they are predicated upon snap judgments.

The things we do in front of others—like making a speech, or playing sports, or leading a meeting—constantly force us to wrestle with thoughts about others’ perceptions of our “performance.” Excessive worry distracts us, resulting in lower performance and less effect. Worse still, excessive worry fractures our sense of dignity and self-worth both in the moment and well after the fact. The same is true of excessive pride.

Public activity courts private sin.

The Bible refers to this category of sin as “the fear of man,” but we might simply say that it’s unhealthy to worry about what others think, to yearn for their approval or to define our value based upon their responses.

With that in mind, here are the 5 most common ways we sin in public:

1. We react to what “they” must be thinking. We see the people around us and—often based on nothing more than their facial expressions or a momentary exchange in the lobby—we conclude that they are being critical, hostile, or dismissive. As a result, we get defensive and begin roleplaying dramatic confrontations with our supposed adversaries WHILE STILL PREACHING (or whatever). Then, the realization hits us that we are being totally asinine—that, in fact, they have never accused us of smuggling Chernobyl pandas into Mexico—and then we are filled with shame.

But the truth is that we have no idea what they’re thinking, and whenever we guess, we’re wrong. For example, as a young man I was so distraught over my lousy sermonizing one Sunday that I left the pulpit in the middle of my preaching. I had been struggling, and there was a domineering elder in the congregation who intimidated me. The more I struggled, the more I focused on him, imagining he wanted me fired. So I quit. On the spot. And ran out the side door. Yet it was that same elder who chased me down and told me I had been doing wonderfully and he was enjoying it. I had seen his grumpy-looking face and assumed he was irritated. But I misinterpreted. He wasn’t irked, he was deeply enjoying the material of my sermon. What I thought was agitation was actually inspiration. God was working in him, and I short-circuited that work because I got distracted by my fears and ran away.

Don’t guess what “they” must be thinking. Just do what God has put in you to do the best you can, without going flaky.

2. We react to our own performance. Let’s be honest: we know when things are going well, and when they are not. We know when we’re performing at our peak, and when we’re going down in flames. And in either case—elation or embarrassment—we get preoccupied. You might think this is only a problem when we perform poorly; but, as a good friend of mine says, “the same gene that allows you to feel like crap when you fail makes you act like an ass when you succeed.”

3. We allow our emotions to affect our performance. To clarify: in this instance I mean that our overall emotional state trickles over into our work, our sport, or our moment to shine. If you’re depressed, or enthused, even overcome with fervor, you’ve got to make sure to keep your emotions in check because they will betray you. This may seem counterintuitive. You may think that only negative emotions need to be restrained, but even good feelings can betray you in front of others because you end up wondering why no one else is as excited as you are, or as prayerful as you are, or as amped as you are. But the truth is, no one else has experienced what you’ve experienced to spark this intense emotionality in the first place.

4. We rest too much on our own spirituality. Three different times I’ve had worship leaders approach me 5 minutes before church and tell me they don’t feel right about leading worship because of their own sin-issues. Really? Five minutes? I applaud their convictions, but question their wisdom. Not because “the show must go on” or because they’ve inconvenienced me; rather, I question their wisdom because their last-minute departure demands a public explanation. At the very least, the other musicians will put together that something weird is going on that kept the leader from the platform. To avoid further weirdness, the band needs to know what’s going on…or at least a part of it. Had the leader(s) come to me earlier, in private, I could have offered counsel and prayerful rehabilitation (possibly taking several weeks or months, but at least it would be in private), but now they’re end up labelled as degenerates or perverts in the eyes of their key volunteers because they turned their private guilt into a public spectacle.

Here’s the truth: we all sin and we all must deal with our sin, and sometimes our sin should disqualify us for a time from public ministry. But, to arrive at that realization five minutes before a public event isn’t a demonstration of courageous repentance so much as it is a revelation of fickle emotionality.

God doesn’t need you to be perfect in order to work through you. He can draw a straight line with a crooked stick. For that matter, in case you’re feeling uppity, he might even prefer someone who acknowledges their imperfections rather than one who pretends they don’t have any.

You’ve got to come to terms with the fact that—No, you’re not good enough, but—Yes, God wants to work through you anyway.

So buck up, beg for forgiveness, and fix whatever it is that’s causing you to squirm—not just so you can lead, but so you can live.

5. We over-count what “we know.” I “know” that our culture does not respond well to oratory, so every Sunday when I get up to preach I have a tape running through my head that says, “This is stupid. No one cares. No one gets anything out of your sermons. Sermons are dumb and you should quit and become a barista.” But the truth is that my knowledge is wrong. The books I read and the research I’ve done should never outweigh the hundreds and hundreds of people who have come to me every year for the last two decades and thanked me for teaching the Scriptures in a way that makes sense. Because, strangely, God continues to work through preachers and teachers and musicians, regardless of what the latest educational science tells us about oratory.

Sometimes God even works through our sermons, independent of our sermons. For example, my friend Ben recently preached on a troubling passage in the gospels about demon possession, only to have a young woman thank him for his sermon on forgiveness. Ben didn’t have the heart to tell her he hadn’t even mentioned forgiveness. He was just glad God did something in her life, even if it wasn’t what Ben had prepared.

And that’s the truth of it all, right there. This whole thing isn’t about you or me or our performance. This isn’t even about the audience or the congregation. We work ourselves into knots over what’s happening in public, forgetting that God can do something—in fact, a great many somethings—with both our best and our worst efforts. Our job is to just do it so he’s got something to work with.

Now the trick will be to do it without sinning quite so much.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018