“Think about something real hard and then don’t think about it at all.”

Don Draper

“Take two ideas that have nothing to do with each other and explore them from all sides…then play with them until they begin to get along.”

Len Sweet

People who manage creatives often believe brainstorming is the best way to maximize the reservoir of imagination at their disposal. They’re wrong.

Brainstorming creates an environment in which people tend to grab hold of the easiest, most oft-proven “safe” ideas. Partially, this is because creatives don’t want to waste their cleverness on something for which they will receive no credit. Partially, it is because the best ideas take time to germinate, and creatives tend to come back and play with these ideas over time. Partially, it’s because people would rather shut up and put up than speak out against an idea that doesn’t excite them or they think is going nowhere.

You can’t just stick a bunch of creatives in a room and shake them up to see what pops out. Like athletes, creatives have their own quirks and proclivities, work flows and skill sets. No one would imagine throwing Brett Favre and Joe Montana on the same team, since they both play the same position (and are really old). Neither would anyone imagine putting LeBron James and Mia Hamm in hockey jerseys and telling them to take on the Canucks.

Individual talent, combined, does not guarantee a winning team.

Why? Because…

- There are different kinds of creative skills, even within the same discipline.

- The differing personalities of creatives will energize different opportunities.

- The differing processes of creatives will cultivate different ideas over time.

- The lack of personal credit in a group project will discourage creatives from weighing in wholeheartedly.

- The frustration of not being in control will take a sizable minority of creatives out of play altogether.

- The people with the best group skills will dominate the group, regardless of their relative merit as creative contributors.

- If the conversation is good, the manager will assume the final product will be good based on the synergy of the meeting rather than the merit of the idea.

- The manager will make judgments about the less participatory creatives—about their lack of enthusiasm, their silly ideas, or about their outright disdain for the process—and draw inaccurate conclusions about their worth as part of the organization.

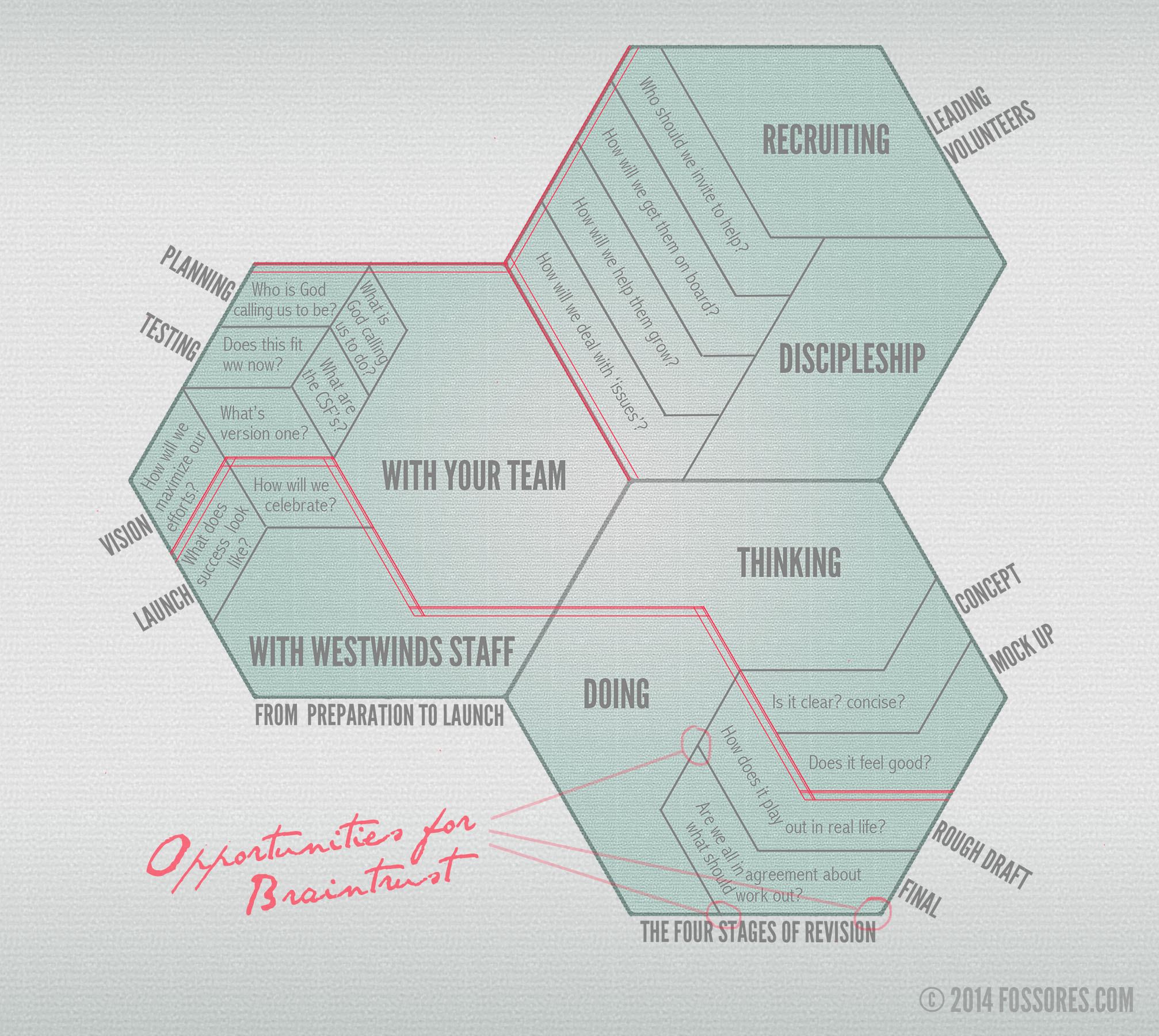

In Creativity Inc., Pixar CEO Ed Catmull describes the best way to get around these flaws as the creation of a “Braintrust,” which requires creatives to work in isolation until they have a finished product—a version one, so to speak. It is the best possible version of their work done in isolation. That version is shown to the Braintrust—a handful of the organization’s best storytellers, thinkers, and producers, who then offer intense critique about what doesn’t work. The creator is then responsible for addressing the issues, or not, as he or she sees fit.

The critical feature here is two-fold: first, the creator must want her product to be the best possible; second, she must be ready to hear the truth. “Candor,” says Catmull, “is only valuable if the person on the receiving end is open to it and willing, if necessary, to let go of things that don’t work.”

Next time, instead of brainstorming to get ideas, try braintrusting to maximize existing ideas to their fullest potential. Your people will take more ownership, more pride, and deliver better results in the process.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018