Once upon a time…

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…

In the beginning…

These words have a mythic quality to them, don’t you think? I don’t mean that they are all – equally – myths, just that the way they sound makes me feel like I’m about to learn something important about who I am and why I’m here in this moment.

They are framing words – words used to set up everything that comes after them. “Once upon a time” precedes the damsel in distress. “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away” comes before Luke and Leia contend with Darth Vader. “In the beginning” presages the fantastic true story of the downfall of humanity, our redemption through Jesus Christ, and our return back to our true selves in him.

These words set the stage for all that we know to be true about Christian spirituality. But what of these words? And, how are we to take them?

Some may choose to take them as history. Some may choose to take them as oral tradition. Some may choose to take them as description. Some may choose to take them as poetry. But I’ve come to read (and re-read, and re-read) these words as something else entirely. I read Genesis 1 as a kind of criticism. Criticism of the disorder in our world; of the selfishness and vanity of our world. Criticism of the emptiness of our world’s lies; and of the promises those in power make to keep them believed. Criticism of any system that removes people from other people; and from their shared world and all who live in it.

And how does it criticize? By name-calling and rough speech? No.

Genesis criticizes by telling us that in the beginning everything was created as it should be…and when we look at the way it is now we know that something has changed; something has gone wrong.

That is the critique: reality.

I don’t think that the Creation poem was written as a pre-scientific description of how the world was formed; rather, I believe it is a prophetic critique of the brokenness of this world. I believe it is a theological statement that speaks of God the Creator authoring the world in perfect love.

I know for some of you this seems like a foreign concept. Many were raised to understand Genesis as one of the books of Moses, chiefly written to tell us God’s version of science and history, but this understanding is likely based more on tradition than solid biblical scholarship. Others have written much on this topic (Walter Brueggemann and Richard J. Middleton just to name a few) and this is not the place to get into an academic discussion about authorship. Suffice to say, however, that the book of Genesis was not designed to contradict 9th Grade Science lectures on evolutionary biology. It has a completely different purpose.

Genesis 1 was likely written by a priest living in Babylonian exile. Priests, in those days, were understood to be mediators between God and humanity. They were the voice of the people calling on God to save them and to honor Him. Priests would have had their work cut out for them. Conquered by Babylon and held in captivity by this foreign power, the people of Judah (separate now from the people of Israel) would have desperately needed saving. But sometimes, a priest made a kind of crossover. Sometimes a priest took on the role of a prophet. Prophets, like priests, were mediators. However, whereas the job of the priest was to speak to God on behalf of the people, the job of the prophet was to speak to the people on behalf of God.

In this “prophetic” voice, the author of Genesis begins to communicate the truth of this world’s origins via the creation poem of Genesis 1. It was a counter-narrative to that of the oppressing forces of Babylon––Holy Propaganda, if you will.

The Babylonians believed they had every right to hold the Hebrew people hostage. Their religion was one of violence and fire. Their beliefs authenticated aggressive and hostile action against their neighbors. For the Babylonians the old adage proved true that “might made right.” Since they could conquer, the Babylonians saw it as their god-given destiny to conquer so completely that their god would be honored in victory. By writing the creation poem, the Priest is calling the Babylonian god a liar. He is calling the Babylonian people fools. He is calling GOD to remember His nature and character as one who brings order-out-of-chaos.

We should be doing the same thing. There are many false gods in our day, and we should be naming and challenging them as a regular part of life. We don’t always need to be explicit about this – just by living the way God wants us to live instead of the way our love-for-money-and- indulgence culture does – but we certainly need to be aware that there is always a war going on for our souls. It’s an ideological war as much as a spiritual one, and it requires us to constantly be aware of the anti-god powers in this world, just as it requires us to defy them. Our defiance of the false gods in this world – gods of commercial and material wealth, gods of empty sex and falsified intimacy, gods of power and dehumanization, gods of worthless allegiance and broken promises – should also be accompanied by a steadfast grip on the True God. We need to remember that God works to heal the world, just as he works to equip us to do likewise.

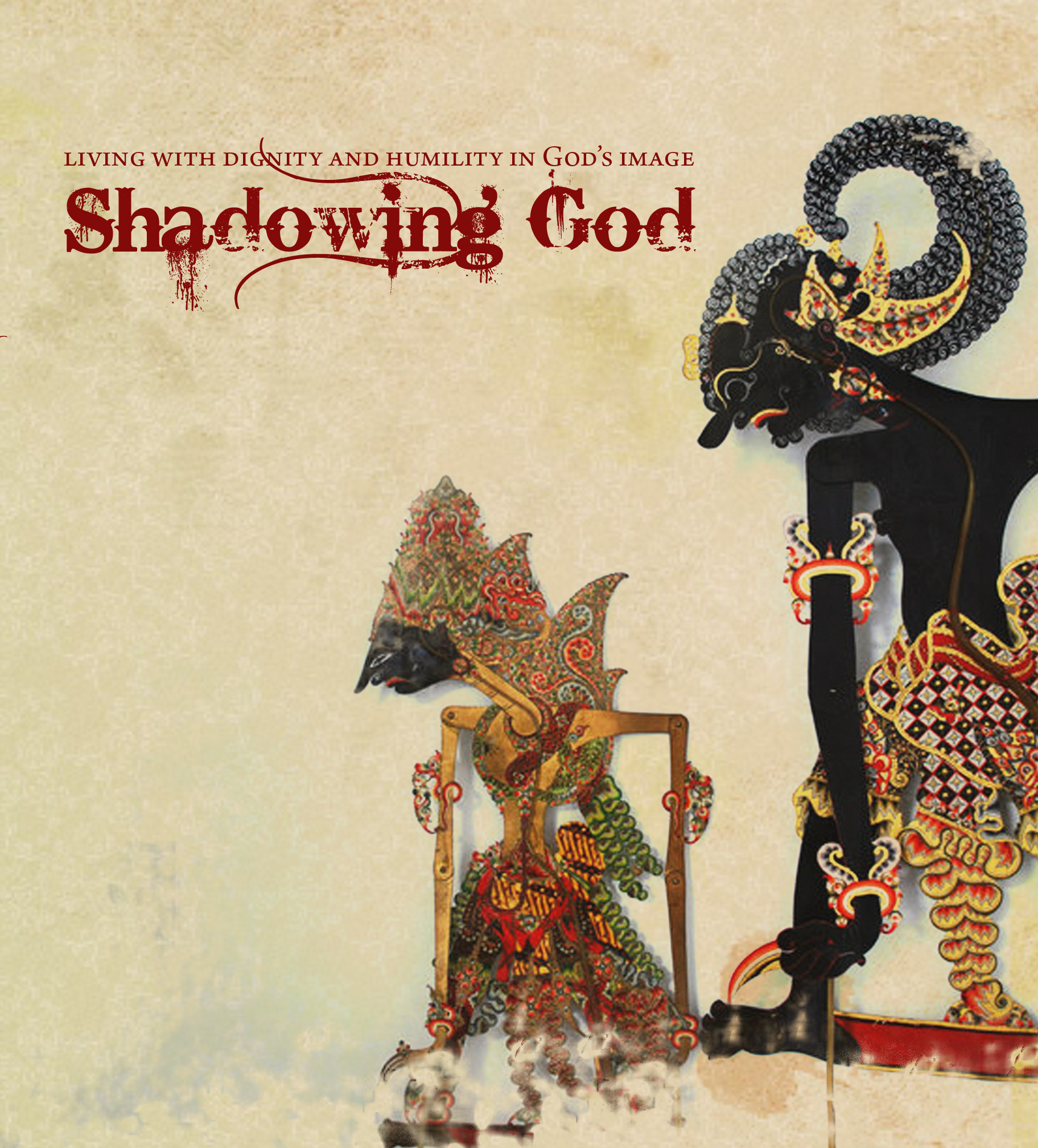

From Shadowing God

fossores

Dr. David McDonald is the teaching pastor at Westwinds Community Church in Jackson, MI. The church, widely considered among the most innovative in America, has been featured on CNN.com and in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and Time Magazine.

David weaves deep theological truths with sharp social analysis and peculiar observations on pop culture. He lives in Jackson with his wife, Carmel, and their two kids. Follow him on twitter (@fossores) or online at fossores.com

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018