Good news: you can make people better.

Bad news: you can only make them better at things they love, care about, and enjoy.

In my earlier years I often tried to help people become more successful, both by celebrating their successes and by pointing out the things they were doing wrong and correcting them. But that approach rarely helped. Sure, people loved my affirmation; but, more often than not, my comments came across as harsh and judgmental despite my best efforts in the other direction.

The truth is there’s no good way to say “you’re doing it wrong.”

Knowing my approach wasn’t effective, I spent time researching positive affirmation and the appropriate ratio of encouragement to criticism. Some experts say it’s 4:1, but I always tried to make it 7:1 just to be safe. There is still a problem with this kind of thinking. Eventually, the people we’re trying to help come to anticipate the criticism and only partially attend to our encouragement. They suspect that our 7 positive comments are really designed to earn us the right to give the 1 criticism we really want to give. As a result, they discard our affirmative statements while they wait for the other shoe to drop. The worst part is they’re usually right. We have to strain to think of 7 positives and constrain ourselves from saying anything more than the single-most important flaw at any given time. It’s a frustrating dynamic for both parties, and though it produces better results, they’re still lacking.

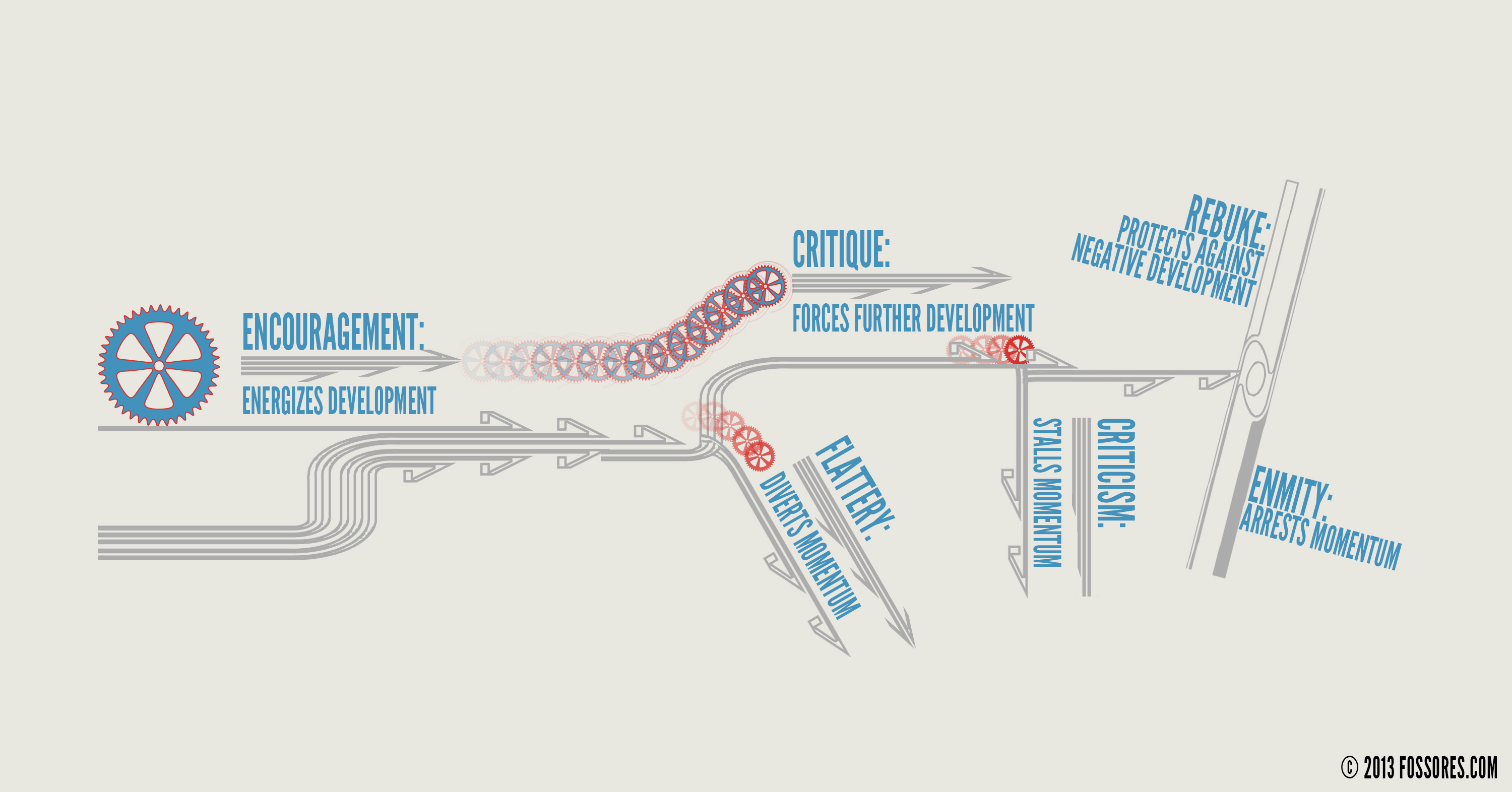

I’ve come to realize that, if you want people to improve, you cannot ever criticize. Criticism arrests developmental momentum. It robs people of the joy inherent in their work. It makes them feel small and scared and communicates disapproval. This is true for employers, managers, pastors, coaches, and teachers.

If you want to help others, you really only have three options: encouragement, critique, and rebuke.

Encouragement focuses on how far someone has come. It acknowledges where they began and the distance they have traveled. You can encourage anybody about anything. And it always helps them feel better and want to continue improving. Whenever we encourage someone about their developing skill, we steward their momentum. We are, in effect, throwing good gasoline on a healthy fire, ensuring it burns brighter and hotter. Even when there are shortcomings and failures that bother us about people, encouragement is always the best practice. Over time, with the proper encouragement, their virtues will so far outweigh their vices that it will seem as though the latter is a fire that has all but gone dark.

But encouragement does have a shadow side. When we over-encourage, we flatter. I love flattery. Whenever someone pays me a huge compliment, I think, “wow…I have never heard that before, and it strikes me to the core.”

However, in any kind of hierarchical relationship, flattery is dangerous because of its inherent intimacy. If encouragement is about development, then flattery is about results. When you see someone working hard at the gym you say, “Way to go! You’re killing it! You’ve come so far!” That’s encouraging. If you say, “Way to go! You look amazing! I can’t believe the size of your chest!” that’s flattery. The former is safe territory for people in leadership. The latter is not.

When we lead people, especially younger people of the opposite gender, must be careful to avoid flattery. Flattery creates an intimate connection between leader and follower that could develop into something inappropriate. Instead, encourage. Say, “You’ve come so far. I love how hard you’ve worked and I think it’s paying off. Keep at it. Everybody’s proud of you.”

But what if everyone isn’t proud of them? What if they aren’t doing well? What if they stink? Isn’t this the time for constructive criticism?

Not if we want them to improve.

The truth is that opportunities are the ultimate motivator. No one gets elevated to a position beyond their competence. If a person can’t perform at the appropriate level, don’t allow it.

But don’t criticize them either.

I would like to differentiate between criticism and critique. Critique, in my way of thinking, is coaching how to get to the next level. If encouragement is about how far someone has already come, critique is about what they need to do to go even further. A good coach offers critique by saying things like, “That’s great! If you want to get to the next level, let me help you work on…” or “You’re almost ready! All we need to do is address…”

Criticism, on the other hand, focuses on barriers rather than opportunities. Where critique says “achieve this and you’ll get there” criticism says “until you fix this, you’ll never get there.” Criticism is anytime you say, “You’re doing it wrong.”

In ministry, when a volunteer makes a video, for example, there are always things we wish they would do differently. In my younger days I would watch and re-watch those videos, coming up with affirmations galore so I could point out what went wrong in other areas. But this process never motivated the filmmakers to do any extra work on the project. I had to learn that any project has a developmental ceiling—this video is only ever going to be 80% as good as I want—but if I’m smart about how I offer critique then the filmmaker’s next project will be far superior. It will still have a ceiling, but the filmmaker will have grown in competency and understanding because they have a clear picture of what it takes to get to the next level. We must teach people how to grow rather than reminding them they are still small.

The final option for people in leadership is rebuke. It’s a strong word and a last-ditch resort. When people are doing harm to themselves or others or about to do something that will cause harm, stop them. You cannot encourage a lemming away from a cliff. You are in a position of authority and have the clout to say, “Stop!”

This will not assist development, but it will stop people from impeding the development of others. If criticism arrests momentum, then rebuke arrests development. But rebuke also arrests negative development. Whenever we have people persisting in harmful practices, we’ve got to step in and get them to knock it off.

Again, this is a last resort. If you have to rebuke someone more than once, chances are you’ll have to dismiss them—even if they’re a volunteer. I want us to think of criticism as “just as bad” as rebuke, realizing they evoke the same response, and simultaneously recognize that rebuke is rarely necessary and, even then, is a measure of protection not correction.

The shadow side of rebuke, though, is personal hatred. We can easily disguise our dislike. We can pick on others, diminish others, and arrest others all the while supposing we’re doing this for their own good.

I’ve done that. Not intentionally. Not recently. But there have been times when both employees and volunteers have driven me crazy. And because I didn’t yet recognize the difference between their need for next-steps and my need to solve problems, I stunted their development and (sometimes) dismissed them from that level of service.

The best way forward, when you have to rebuke, is to go straight into critique afterwards. This, of course, will give you the opportunity to encourage. “You stopped when I asked, which is great. I applaud your sensitivity and willingness to learn. You’ve got a bright future there, so long as we keep stoking that quality.”

And once you’ve traveled back from rebuke through critique to encouragement, you’ve already begun stewarding their developmental momentum once more. Encouragement builds momentum.

And that’s the point. When people know what they want and know we want it too, there’s no stopping the internal engine of their development. They’ll want to grow because growing feels good, because growth is its own reward, because growth is rewarded and energized and recognized.

You can only help people in the areas they love, care about, and enjoy.

fossores

Related posts

Categories

Category Cloud

Tag Cloud

Recent Posts

- Victors and Victims November 6, 2018

- 3 Hacks for Happiness October 29, 2018

- Hope Against Death September 20, 2018

- The Shape Of The Cross September 19, 2018